Published: Sep 23, 2025 by

Background

OutdoorLads are a UK group for gay and bisexual men to #GetOutMore in the great outdoors, which I’m a member of. We regularly have “BIG Events”, where we have an evening disco - usually themed! OutdoorLads has its own equipment for this, but it was over 10 years old and was due for a refresh. Since I seem to have inadvertently become known for knowing lots about tech, I was asked to take the lead on this. The whole refresh is a whole other story, so in a nutshell - with a very thorough spreadsheet we ended up with an absolutely awesome setup that is louder and better sounding than the old system, and much lighter too! And most importantly, within budget.

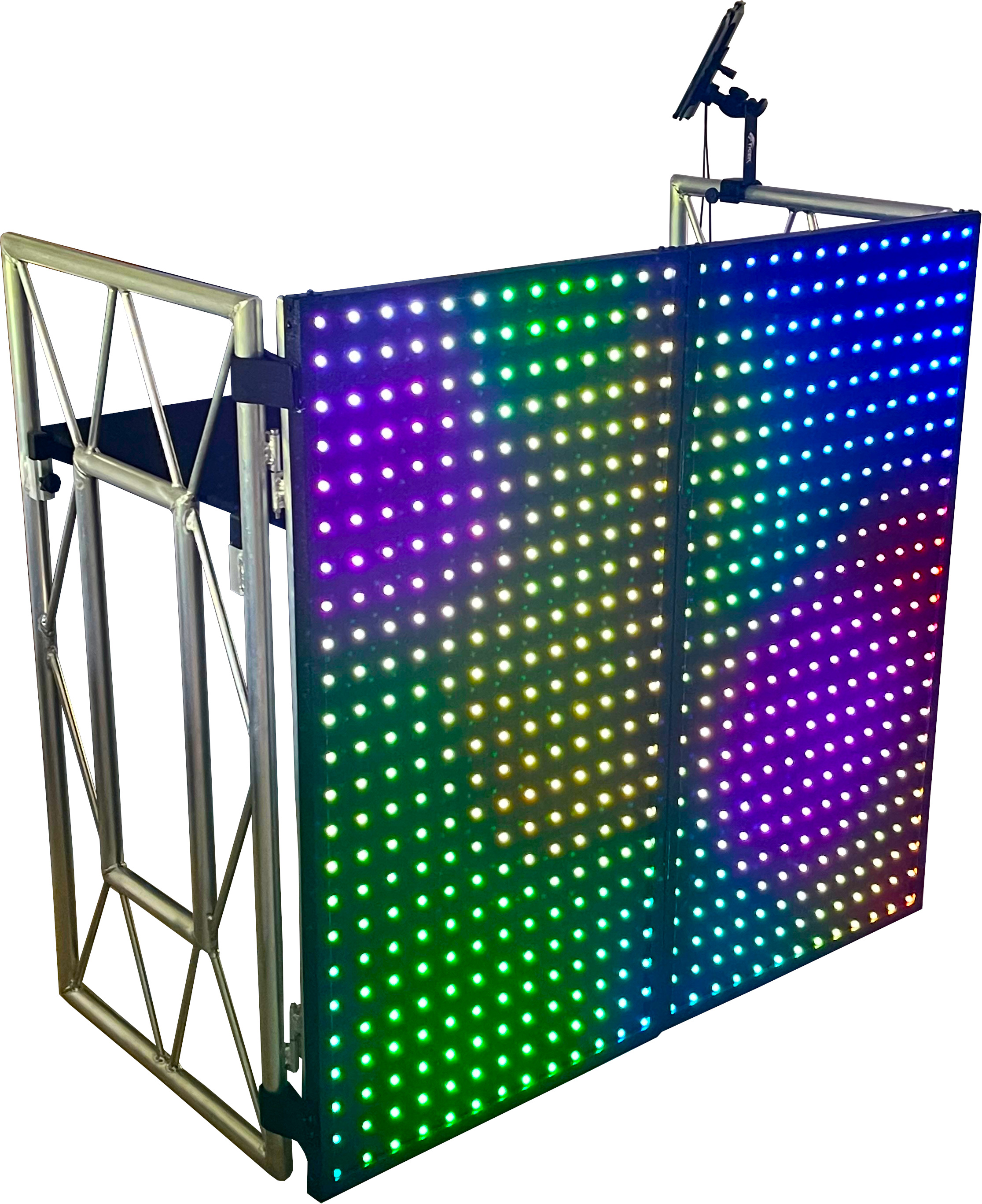

Part of this new setup was a new DJ Booth, which is a truss system - It’s very light weight and is really easy to set up, but it looks so boring! I wasn’t happy with this, and with my love for LEDs and visuals, I knew exactly what I wanted to to.

The Idea

The front of the DJ booth, in my mind, was SCREAMING for a LED Matrix facade to make it really pop. As expected, there were no accessories for the DJ Booth, and if you want one of these, they’re usually made bespoke, and are quite expensive!

So this is where James makes one bespoke, and lucky for OutdoorLads, the parts aren’t expensive and my labour of love is free.

Since all the equipment is moved around from venue to venue, the LED Matrix also needs to be transportable - this means not occupying a great deal of space, and be rugged. The design direction I went down, was to have a foldable LED Matrix, that folds in half a bit like a laptop. When open, it fills the entire front of the DJ booth, and when closed, the LEDs are protected inside, and some claps keep it shut.

Requirements

Before detailing the design and build, the following requirements are what I had identified for this project:

- Must fill the whole front of the DJ Booth, and be able to be securely attached

- Must be able to fold up to aid in transportation and storage

- Must be rugged to withstand transportation and drunk people

- Must be easy to setup by non tech-savvy people

- Must have a decent pixel density (bit of a wishy-washy requirement)

- Must have a selection of kick-ass visualisation effects

- LEDs must be RGB, and be as big as possible

- LEDs must be able to be driven rapidly to sustain a video-quality refresh rate

- Total cost of parts must be below £300

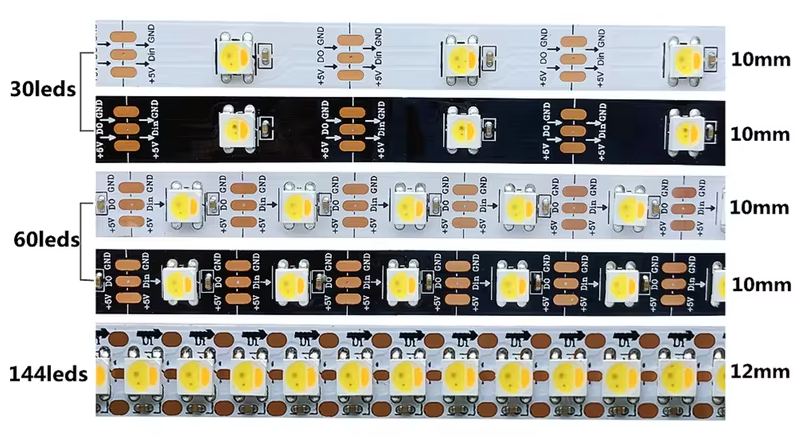

I’ve already used addressable LEDs before in the past - they’re awesome! So using them for this project was a decision I had already made. There’s various different types available - I wasn’t going to bog myself down with one particular type, instead, I decided to look at what different addressable LED packages are available, i.e. the physical LEDs. I’d then chose the addressable LED type based on what is available in the package I want.

Designing Foldable Frame and LEDs

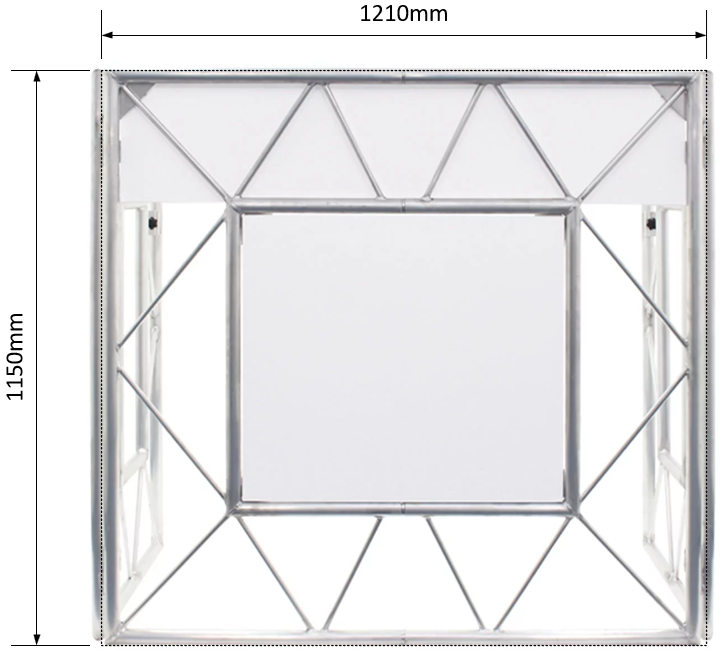

First thing is to get an idea of how this LED Matrix will be constructed. It needs to open out to fill the entire front, and have the LEDs mounted in such a way that they are sturdy and look good from the front, and hide away/protect the wiring and electronics of the LEDs. The Truss DJ Booth that this is being designed for is shown below:

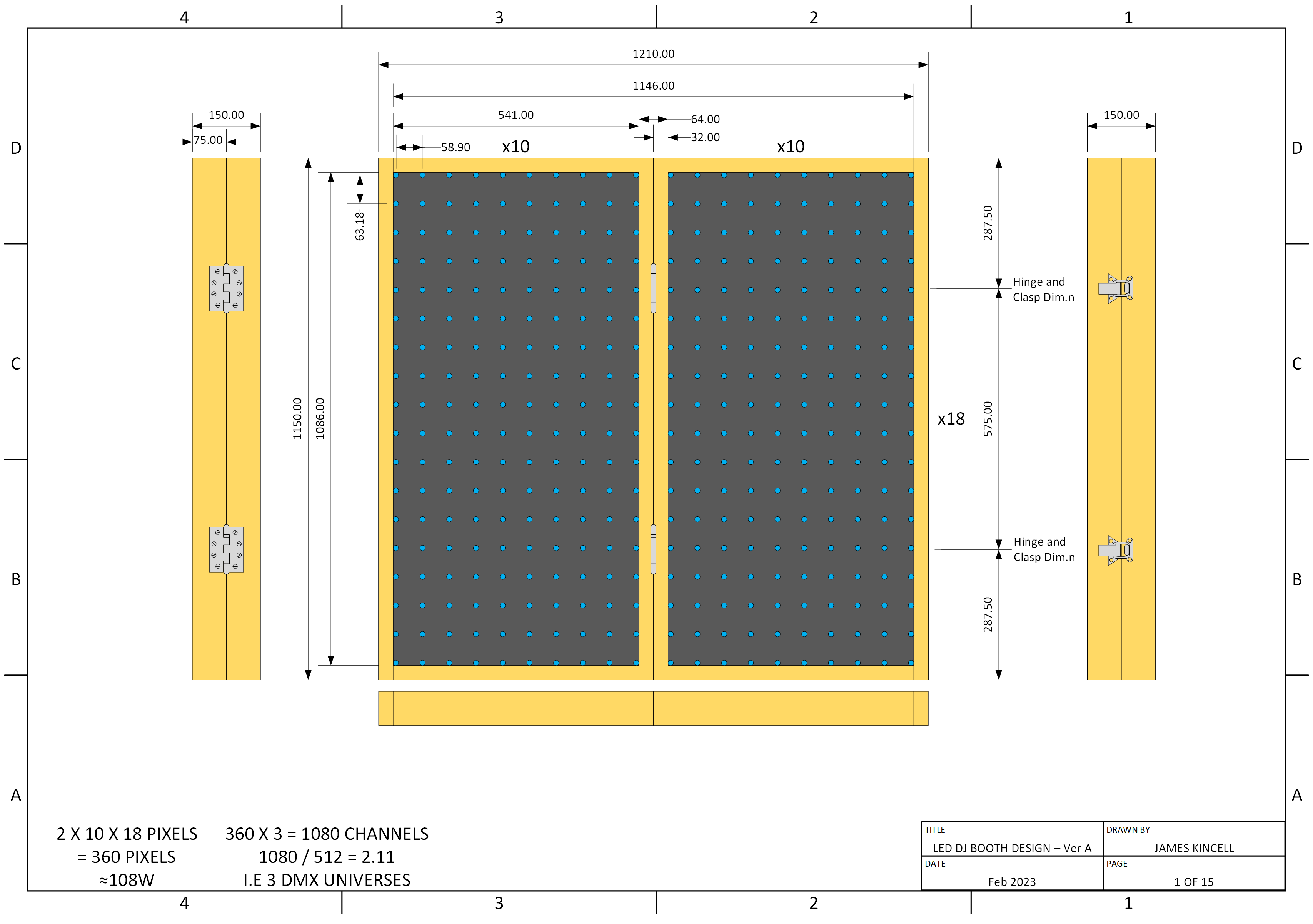

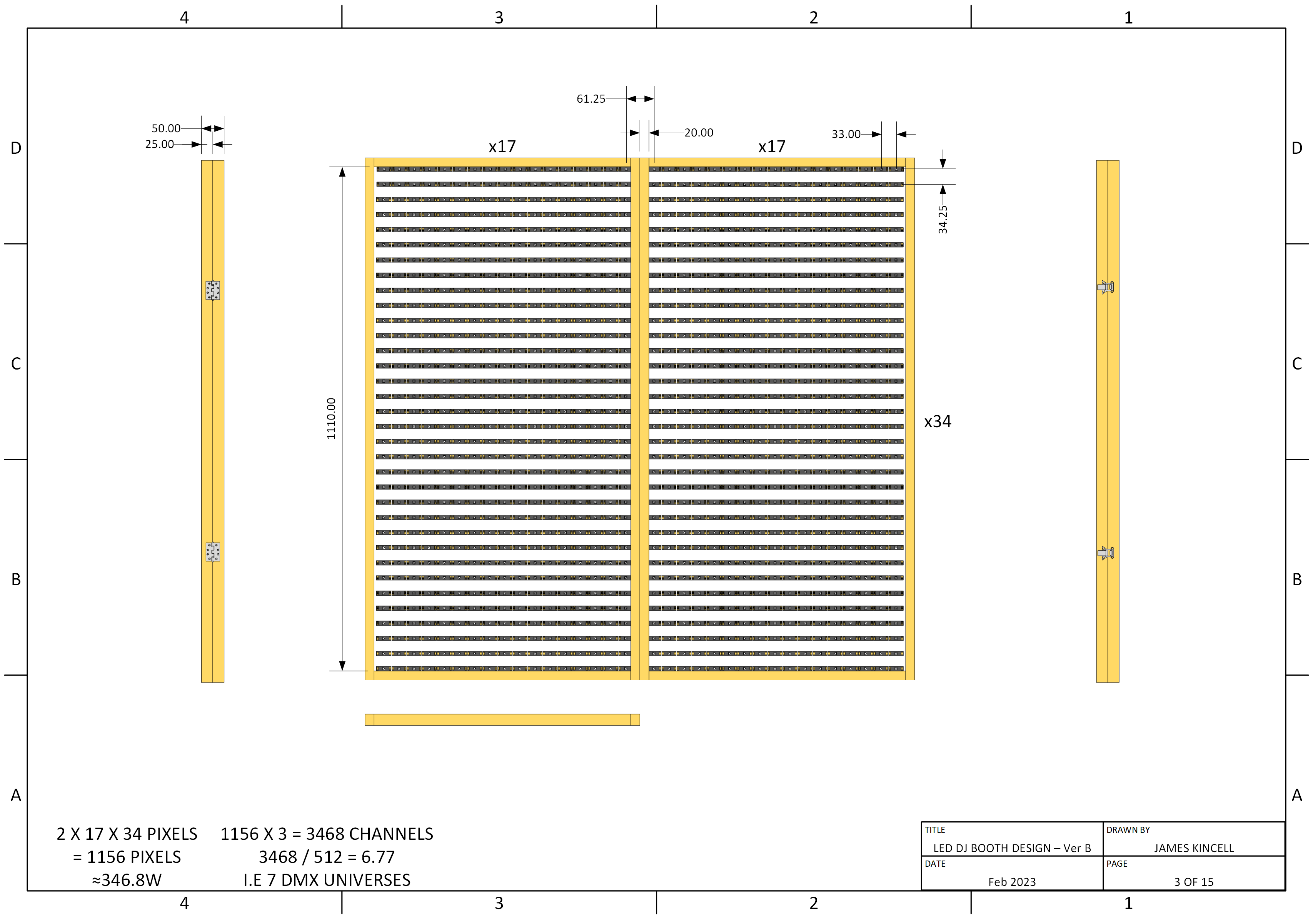

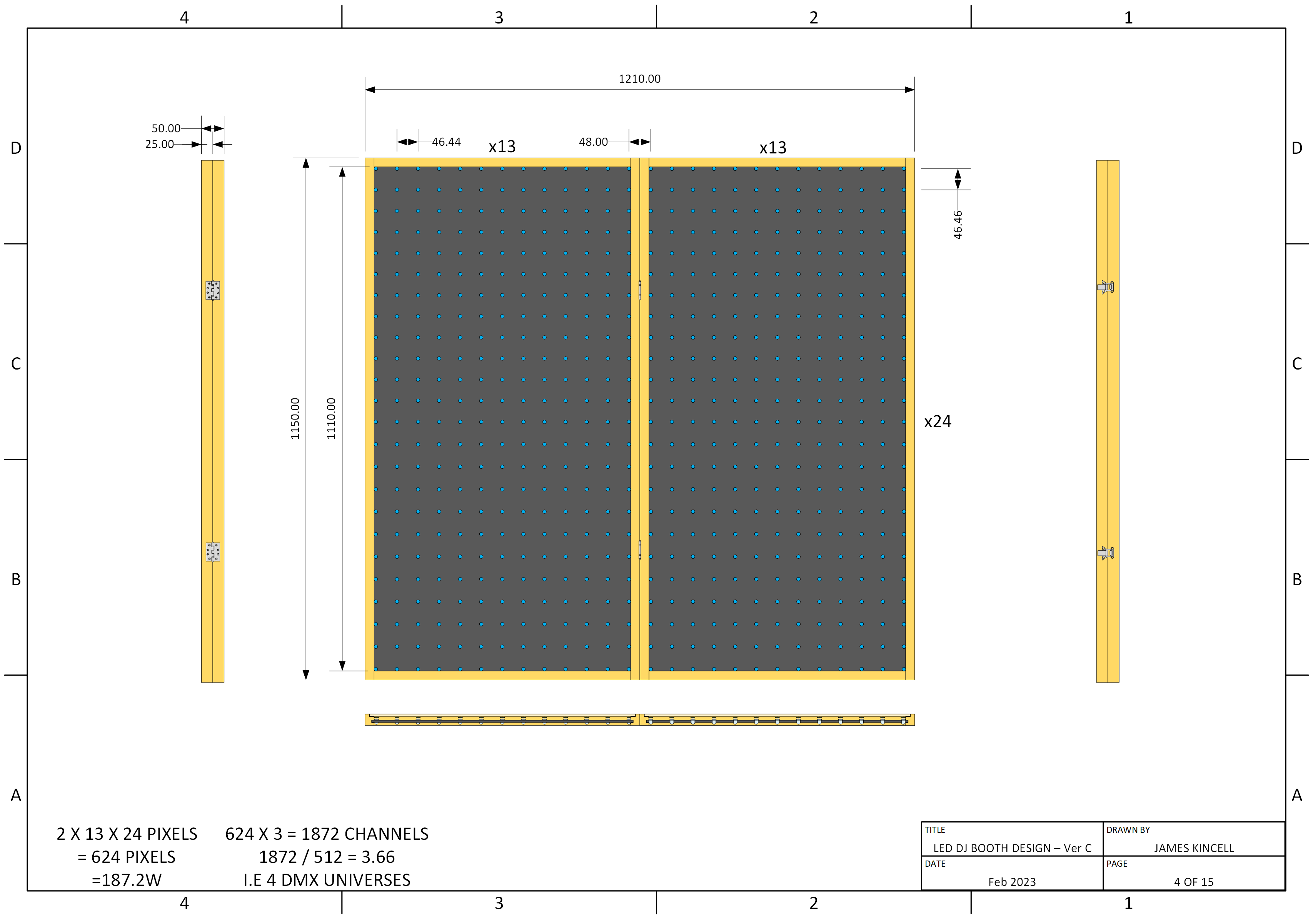

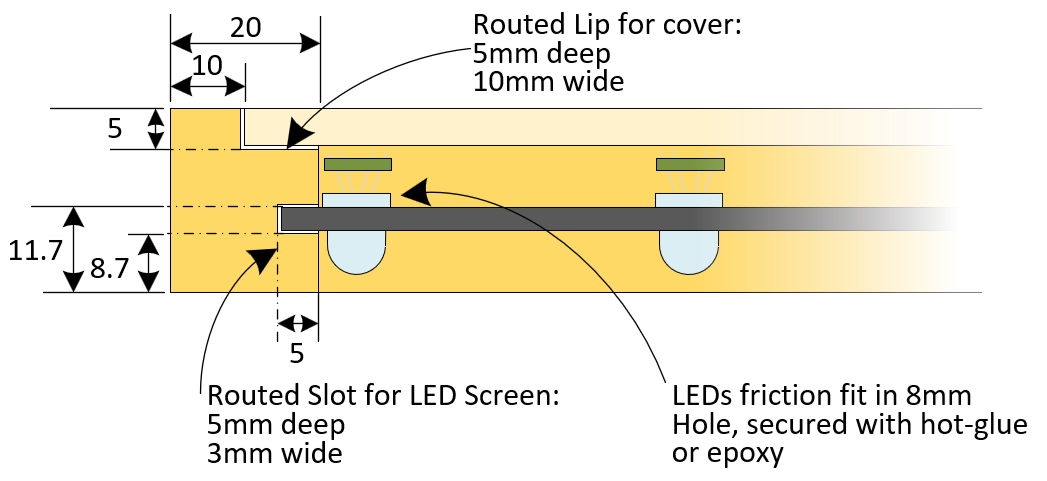

As with most designs that are physical, I did some simple 2D modelling using Microsoft Visio (I always feel some shame in using Visio! I use it all the time at work and I can use it really well). I did this so that I can get a visual indication of what the LED matrix will look like. As mentioned, I want the pixels (I’m going to refer to the LEDs as Pixels in when in the context of the Matrix) to be spaced such that pixel density doesn’t look too “empty”, so that the effects look good. Another key aspect here, is that the physical build will have a structural frame, and due to the matrix being foldable, there will be frame in the middle, two frames in fact - one from each side. I don’t want the frame to add any extra spacing between the pixels on both sides, I want the pixel spacing to be uniform across the whole matrix. So, the 2D models allows me to identify the spacing between the frame join, which governs the minimum spacing.

(By the way, all measurements are metric. mm unless otherwise stated).

Design A

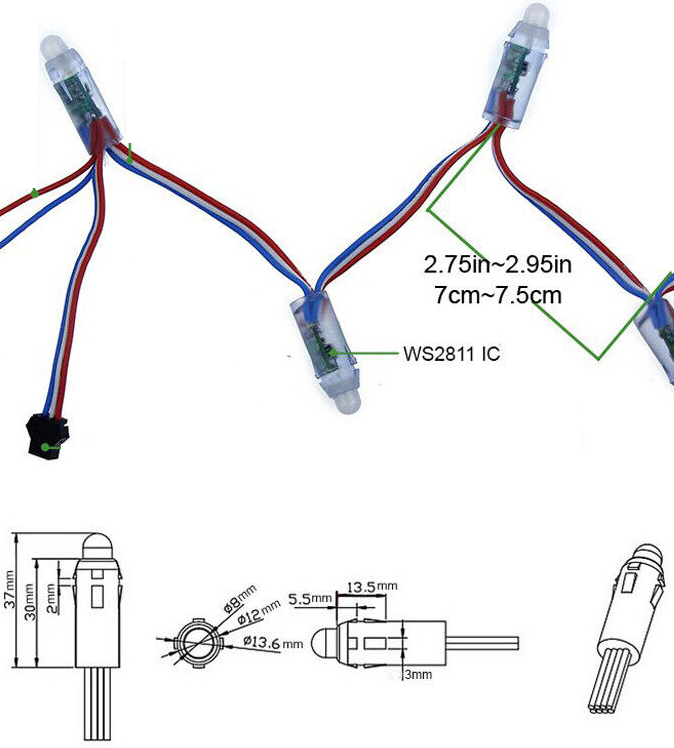

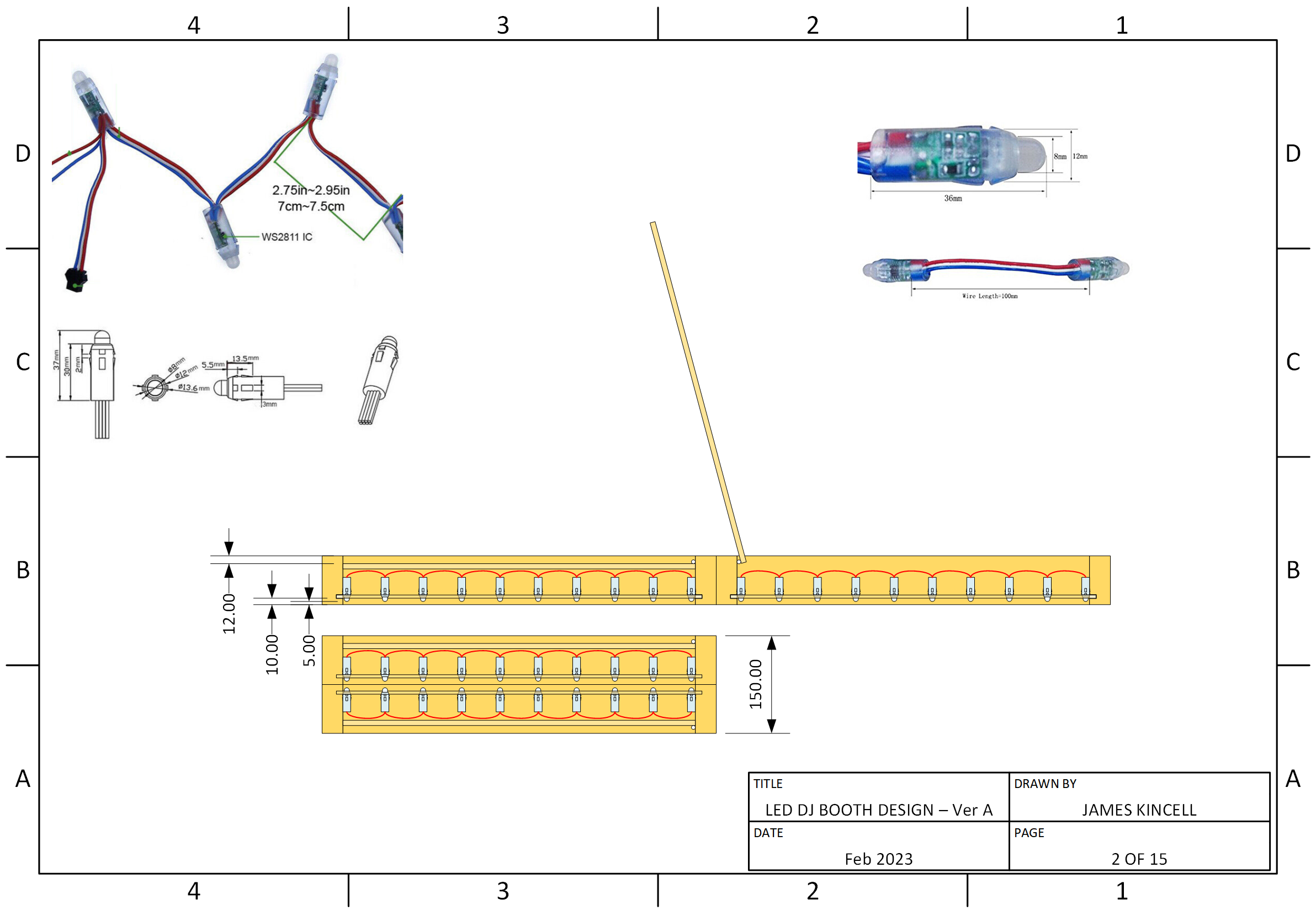

The first design is based around addressable LEDs that are in a string - a bit like Christmas lights. They are 5mm RGB LEDs soldered to a PCB that has the addressable controller, epoxy encapsulated in a mount (I use the word mount loosely, it’s a friction fit mount). These were my first design since I’ve used these type of addressable LEDs before in a project that I did to make some Pac-Man prop boards.

The good thing about these, is that I can space the pixels however I please, to both get the right pixel density, and also fit within the panel size evenly. The down side with , is that they are very deep, so the panels needs to be able to accommodate their depth.

For this design, in order to be able to accommodate the depth of the LEDs, I chose to use 75mm by 32mm timber. I already was not happy with this design - the folded thickness is 150mm - that’s 15cm! That’s too big, clumsy, and heavy. Also, the frame causes a gap of 64mm between the two panels, and the best spreading I could design here was a inter-pixel distance of 58.9mm. This means that there will be a slightly bigger gap between the LEDs at middle, which will be obvious. Not happy with this.

| Thickness: | 150mm |

| Inter-pixel Distance: | 58.9mm |

| Frame Gap: | 64mm |

| Resolution: | 20 x 18 |

| Total Number of Pixels: | 360 |

| Approx. Max. Power: | 108W |

Design B

The first design is good and allows flexibility in pixel density, however it is too damn thick! This makes it difficult to store and transport, plus makes it more clumsy. My second design is with a thinner design, using addressable LED strips - you’re probably familiar with these types of things, they are LEDs etc. mounted to a flexible PCB, and usually come with a self-adhesive back, and they can be found in water-resistant versions where they are covered in a flexible encapsulation. These are really thin! So it means I can make the frame thinner than with Design A. The downside though, is that they have a fixed spacing between the pixels, so less flexibility when designing in to the frame.

30 LEDs/m ≈ 33mm between LED centres

60 LEDs/m ≈ 17mm between LED centres

144 LEDs/m ≈ 7mm between LED centres

For this design, since the strips are thin - about 2.5mm, the frame can be much thinner than Design A. For Design B, I chose to use 25mm by 20mm timber. This results in a folded thickness of 50mm, i.e. 5cm - that’s a third of the depth of Design A! So this is much thinner and lighter. With this timber, the frame causes a gap of 40mm between the two panels - this means that the only strip type that would work is the 30 LEDs/m type, with a distance of about 33mm between the pixels. This is annoying, since the pixel distance is closer than the frame gap of 40mm, so it would mean that there is a bigger gap between the pixels at the middle seam, something I really want to avoid. To make matters worse, it isn’t possible to get the spacing the same in the vertical axis, and it would mean a vertical pixel spacing of 34.25mm.

So, this design already has it’s down sides despite being thin. And there’s more… If one pixel fails in the future, it would be very difficult to replace a single pixel. The LED strips would have to be attached using the pre-applied self-adhesive tape. I have very little confidence that this would last, and fear that the panels would fall apart too easily, unless a clear perspex front was added on the front, adding to weight and cost, and making it even more difficult to replace a pixel. And then for the final negative point, I think the strips would look a bit cheap and amateur.

| Thickness: | 50mm |

| Inter-pixel Distance: | H: 33mm, V: 34.25mm |

| Frame Gap: | 40mm |

| Resolution: | 34 x 34 |

| Total Number of Pixels: | 1156 |

| Approx. Max. Power: | 346.8W |

Design C

Okay so we’re not off to a good start with the first two designs! I thought I was a bit stumped, but there was something in the back of my mind - the Design A LEDs gave great flexibility with pixel spacing, and looked more professional, but it was the damn enclosure thing that they are encapsulated in that is causing the problems. If I could have those LED strings without the mounting encapsulation thing, that would probably be perfect.

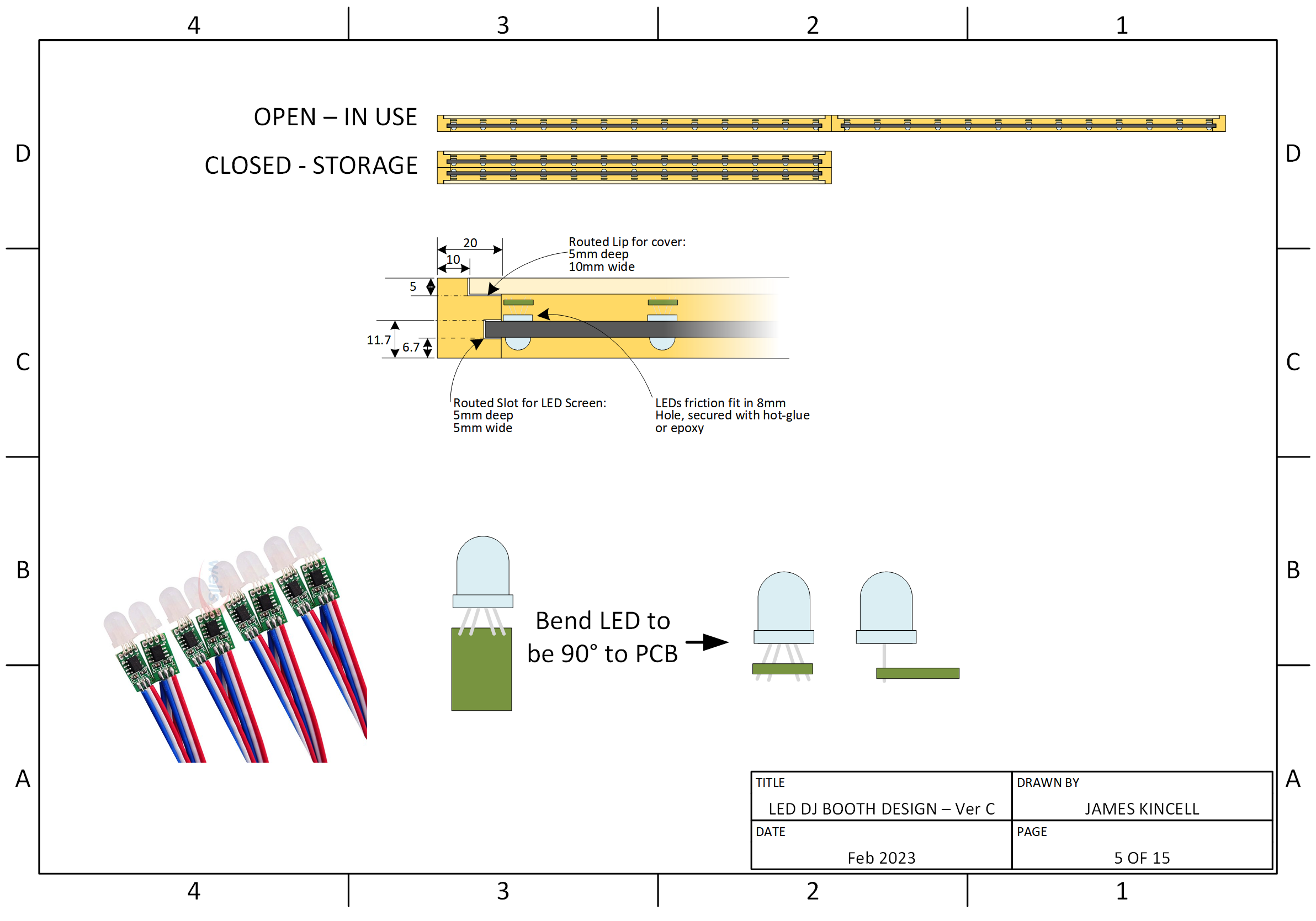

Well, after lots and lots of trawling of the internet, it turns out you can indeed get the Design A LEDs in their raw form, but they were hard to find! With these, the LED is bent 90° as though they are ready to go into the plastic mounting encapsulation thing, but I knew that I could bend the LEDs back to their original position, which would reduce their depth. Plus the lack of a mounting bezel on the LEDs means that the LEDs on the middle can butt up to the frame, to reduce the spacing caused by the middle of the frame. The addressable LEDs in this form factor use the WS2811 IC.

This design combined the positives of Design A with the Positives of Design B:

- Less bulky design, 50mm thick when folded

- Individual LEDs that can be spaced however I want. Can avoid the visible gap of the middle, and the LEDs can be more easily replaced should one of them fail in the future.

With this design, when the LEDs are butt up to the edge of the frame in the middle, the horizontal pixel spacing is 48mm. While it is possible to make the rest of the pixels spaced the same, it meant that the outer edges had no pixel, and it looked odd. As a compromise, I made the pixel spacing 46.44mm, which allowed me to horizontally squeeze in 13 pixels in a single frame, with the middle pixels only being spaced by 1.56mm more, which I don’t think will be noticeable. I was also able to fit 24 pixels in the vertical direction at the same pixel spacing of 46.44mm.

| Thickness: | 50mm |

| Inter-pixel Distance: | 46.44 |

| Frame Gap: | 40mm |

| Resolution: | 26 x 24 |

| Total Number of Pixels: | 624 |

| Approx. Max. Power: | 187.2W |

Chosen Design

It’s probably no surprise that Design C is the winner! To justify this…

Firstly, The LEDs for this design allow the frame to be a reasonable size, such that the frame is rigid yet not big and clunky. The smaller frame reduces the frame width in the middle, meaning the pixels can be reasonably dense. The reduced frame width means that the distance inter-pixel distance (between the pixel centres) in the middle of the panel are 48mm, while the rest of the pixels have an inter-pixel distance of 46.44mm. This means that there is only a marginal difference in pixel spacing at the middle, which shouldn’t be noticeable. The pixels can be mounted in a panel of sheet wood, which has a more professional appearance than LED strips.

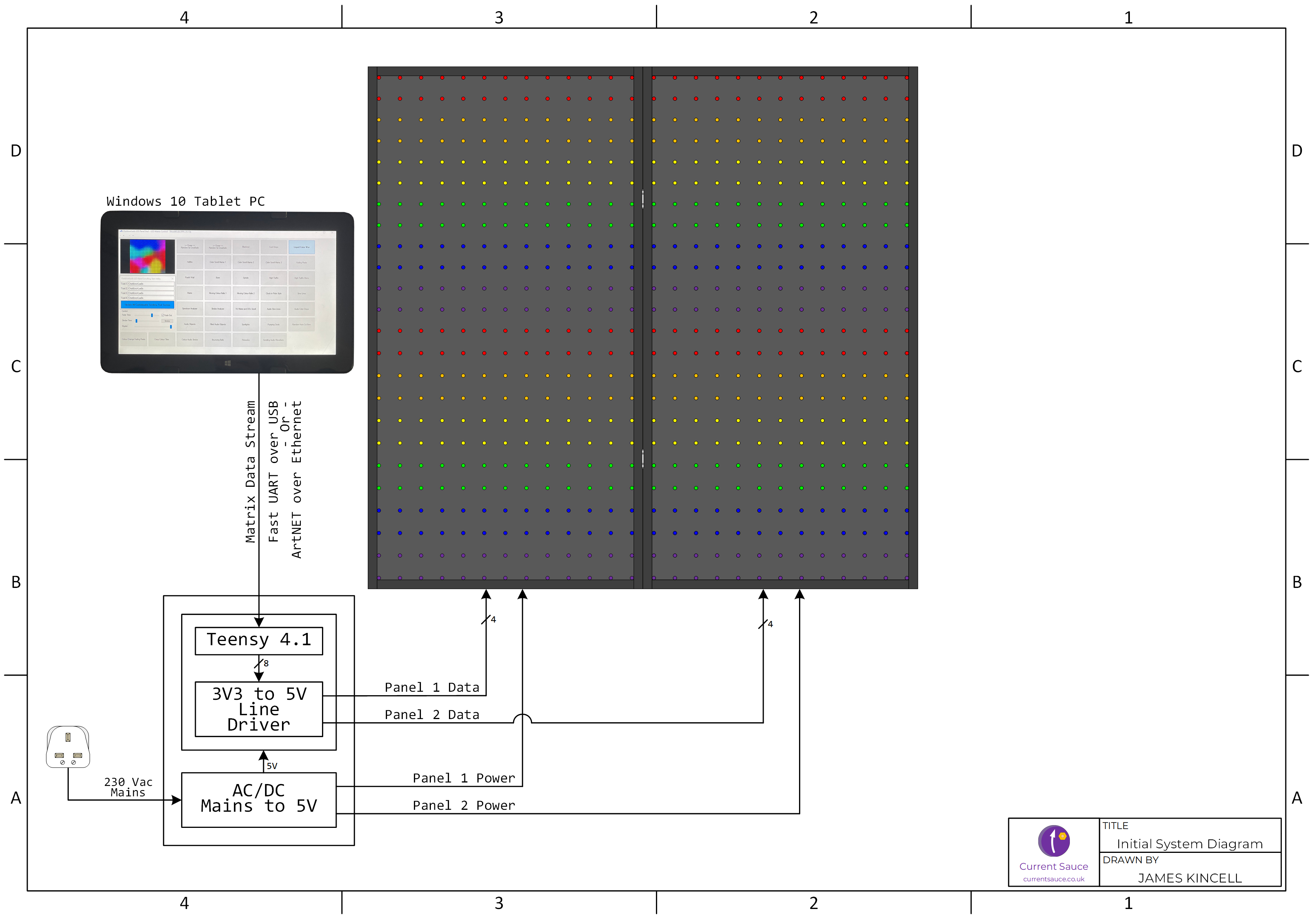

Driving the Pixels

Now that the physical aspect of the design has been realised, albeit in 2D CAD, I now need to design a system for driving the pixels. As mentioned, I’m familiar with addressable LEDs, I’ve used them quite a lot in the past. But, I have always driven them in a single chain from one output on a microcontroller. This design has 624 pixels - it certainly isn’t a crazy amount, like Design B was, but this is a significant amount of pixels and I want them to be able to refresh quickly to be able to display the effects nicely.

And speaking of effects, where are these going to come from? Well, while doing my research for this project, I found the Jinx! Application from live-leds.de - this is a super powerful piece of software for driving LED Matrices - it has a tonne of built in effects, plus you can create your own too using the existing effects as building blocks. And it is free! This seemed perfect. It does mean that the effects are created on-the-fly by a PC, with numerous connections/protocols available. So with this, I need to build some hardware that sits in between the PC and the LED Matrix.

Speaking of the PC, I was chatting about this project to a friend, and he very generously donated me a Dell Venue 5130 tablet. Annoyingly, this has an Intel Atom 64-bit processor, but Dell in their wisdom have never released BIOS for 64-bit operation, so it is stuck in 32-bit mode! Not to worry, shouldn’t be a problem. I used Windows 10 Debloater to strip out unnecessary bloat in Windows 10.

So, I need to build hardware needs to receive the effects from the PC, process, and output the addressable LED signal with WS2811 protocol, and power all the pixels. So how to drive the pixels? My past use of addressable LEDs have always been quick projects with low pixel count, so I have got away with using an Arduino, but an Arduino can only really drive one output channel at a time. You could spread them out onto different channels, but there is not a massive performance change with this. Let’s crunch some numbers:

It takes 30 μS to update one pixel, so with 624 pixels on one channel (i.e. all one continuous string), it takes 19 mS to update all pixels. That means that we would have a refresh rate of 53.4 fps. On the face of it, that is not too bad - to put it in perspective, the refresh rate of a typical LCD is 60 fps. There is a big but here though - this is assuming that the microcontroller is doing nothing at all other than updating the pixels. This is simply not going to happen - the microcontroller is going to be receiving the live stream of data from the PC, processing it into a pixel map, and outputting with the WS2811 protocol. Plus this doesn’t even consider any housekeeping functions that I will probably have too. So, the theoretical value of 53.4 fps isn’t going to be realised with this approach, and this doesn’t factor in the 16 MHz clock of an Arduino.

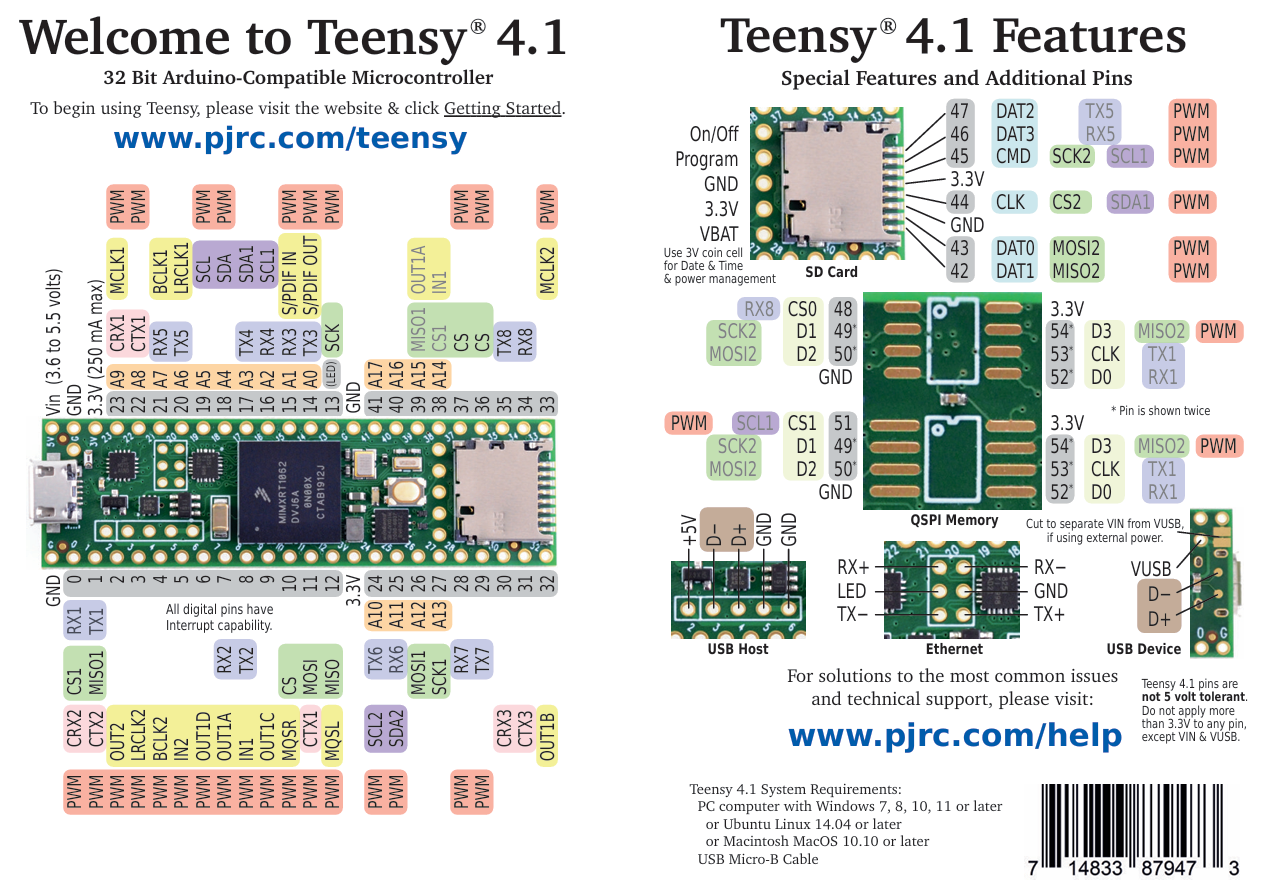

But not to fear, I had something in mind all along! Enter Teensy 4.1! I’ve been wanting to use a Teensy for a while, but never had a project that required this level of performance, so I was super excited that I finally had a use-case for one. The Teensy family of microcontroller boards are fantastic, They’re a family of ready to go microcontroller modules similar to an Arduino Nano, but use really sweet microcontrollers. And if that wasn’t already great, they are also Arduino Compatible, so you can develop your code in the same way as you would an Arduino. Although I can program microcontrollers in their native programming environment, i.e. in the Vendors IDE with Bare Metal code, I already have a fairly big task here that I am doing in my spare time, so I felt that it was an acceptable “cheat” to program in the Arduino environment to get this project finished without unnecessary complications.

So why the Teensy 4.1? Well, it has a wealth of features that are going to make this project as pain-free as possible. For a start, it uses a 32-bit ARM Cortex-M7 microcontroller from Freescale, at a whopping 600 MHz. This means that the processing of the data, protocol conversions and housekeeping is going to occupy a significantly less amount of time than it would on a 16 MHz Arduino. The USB is fairly clever too - should I chose to use UART over USB for the data link, I’m not actually limited by conventional USB to UART speeds - when using USB UART on a Teensy, although the data is UART, the data is at native USB speeds; the any baud rate specified is a dummy parameter, it will use native USB speeds. This means that a USB UART connection is actually a reasonable option here. It also has 10/100 Mbit Ethernet, which is needed if I chose to use ArtNET as the communications link from the PC. Another handy feature is an SD Card slot that uses a native communications - quite commonly SD cards are used with microcontrollers in SPI mode (which I have indeed done before), and this does not operate very fast when compared to operating an SD card in its native SD communications. So, should I chose to have some built in effects, I could store these effects on an SD Card, and not have to worry about the SD Card read operations occupying too much processor time.

All sounds good so far doesn’t it! But I haven’t got onto the what was the main reason for opting for the Teensy 4.1 - OctoWS2811. By using some clever very use of DMA-based data transfers on the ARM Cortex-M7, the OctoWS2811 library, written by the Teensy’s creator Paul Stoffregen, allows the Teensy to write to 8 WS2811 channels simultaneously! And, with minimal processing impact. This is just incredible - It means that I can spread the 624 pixels across 8 channels, and with the very high processor speed, the refresh rate will be super high, higher than I would need in fact.

The figure below shows a very simplistic overview of the system. The Teensy 4.1 will receive the data stream from Jinx! running on the Windows 10 tablet computer. I’m not concerned about the Windows 10 end-of-life since this tablet will be disabled from connecting to the internet (i.e. Wifi disabled in BIOS). The data stream will be delivered either via ArtNET over Ethernet, or via UART over USB - remember, the USB UART on a Teensy 4.1 runs at native USB speeds, not conventional UART speeds. The Teensy will then output eight WS2811 channels; four channels for each panel, meaning that each panel will have four groups of pixels. The Teensy is a 3.3V device, meaning that the GPIO ports can only output 3.3V level logic, whereas the WS2811 LEDs are 5V logic. This is no trouble, it just means that I will need to have 8 level converter channels to buffer the 3.3V logic to 5V logic. To be able to power the system, a suitably sized PSU will be needed - I’ll cover that shortly!

Back to the Build

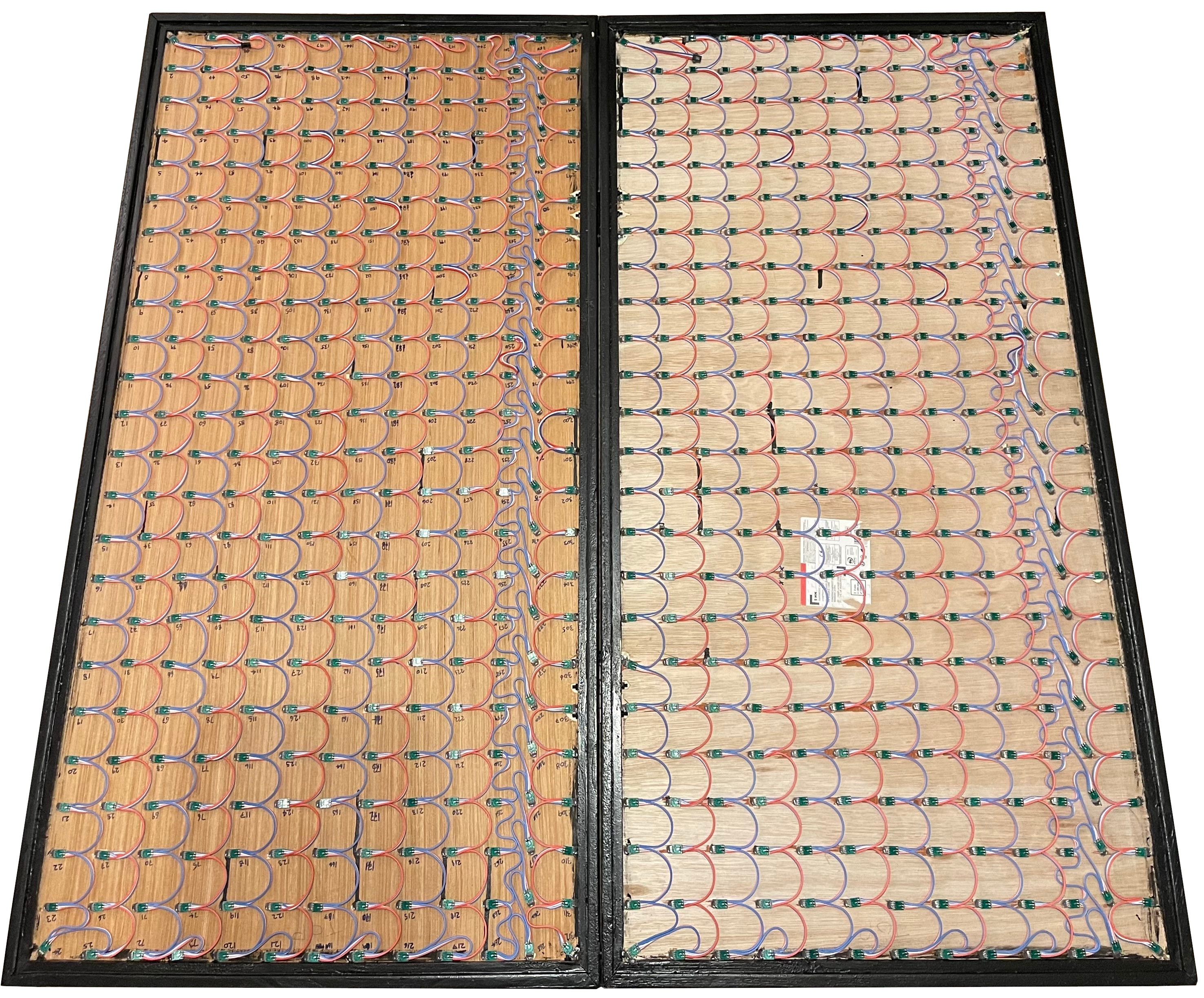

With the necessary design work done, now is the time to make this a reality! Since I already had the Design C 2D drawing, I just needed to do the woodwork. It is quite similar to a photo frame to be honest. It is constructed using 75mm by 32mm timber for the frame. The back is a sheet of 5mm plywood. In the design, the LED pixels are also mounted into a 5mm sheet, but I decided to down-size this to 3mm Plywood.

To make the frame, my friends Pete and Phil of Crazy9 Mobile Crazy Golf very kindly let me use their Stockport Woodworking Studio (Pete helped me while Phil was busy making a Plinko Game for their mobile golf course!). We used a table saw to make the details needed for the mounting of the sheet wood. I also used the picture-frame idea and made the corners at 45° too. The final result is exactly what I had envisioned, really pleased with it. Marking out 624 holes and then drilling them was less fun though.

I thought that drilling 624 holes was hard work, I take it back, fitting 624 LEDs was a real chore. I spent time making sure that the cables were routed nice and neatly, it means that the cables are under less twisting and bending stress, improving reliability, considering this will be transported around frequently. It also makes it much easier to work with, since I will be routing data and power lines in addition to these LEDs. The holes were drilled at 8mm, which is the same size as the LEDs. I did a practice hole first to check how well the LEDs fit in the hole, and it turned out that they fit really well; there was a lot of friction to get the LEDs in the hole, so I had confidence that the friction fit was all that was needed to hold the LEDs in in place. There were only a couple that were a little questionable, so I put some hot glue on those just to be safe. Not needing to glue every single one in place was good for two reasons - firstly, it saved me a lot of time and mess, and secondly, from a maintenance perspective, should I need to change an LED if one fails, I don’t have to de-glue them.

Pixel Talk

Since the LEDs are in a string, it makes sense to wind the LEDs up and down - this makes the wiring simpler, and most importantly it keeps the distance between the LEDs the same distance. I don’t want to make the distance between the LEDs any longer, since long wires are the enemy; the output of each WS2811 pixel is a buffered output, but long wires make the signal susceptible to signal degradation. Thankfully, the Jinx! software is able to handle pixels arranged in this snake-lines pattern. I planned to have the connectors at the bottom of each panel, so this means that the data signals will originate from the bottom, so this means that the snake-lines will run bottom to top, top to bottom etc., so the pixels will be in columns, not rows.

Each panel will receive four data lines, meaning that the 13 columns of pixels need dividing up into channel groups. 13 isn’t a nice number for that! The best way to do this would be to have 3 groups of 3 columns, and one group of 4 columns. I wish that I had made this realisation before putting the LEDs in, because doing it this way would mean that I have to break up the snake-lines to re-start at the bottom on the 4th, 8th, 12th etc. columns. Instead, with the way the LEDs are fitted, these columns are a flow down, not a flow up. Damn! So with the arrangement I have, the I need even number of columns in a group. The arrangement I went for is three groups of 4 columns, and one group of 1 column per panel. Overall, this means six channels with 96 pixels, and two channels with 24 pixels. A picture speaks a thousand words, so this is shown below:

![]()

With the start of each channel group starting at the bottom, I connected wires to the start pixel in each group, and routed the wires to the middle in an empty gap, in preparation for a connector to be fitted. I also prepared the power wires to an empty gap on the bottom right, in preparation for a connector. The daisy-chain of the LEDs carries both the data and power, but one thing you have to watch out for with a string of lights like this is voltage-drop on the cable. The individual LEDs are each interconnected with wire, which will have a very small amount of resistance. Current in a resistive element causes a potential difference - Volts - simple Ohm’s Law. This means that over a length of cable, what started as 5V will gradually decrease. The voltage-drop is very small, but over a long length, this adds up, and it manifests itself as the start of the string being brighter than the end of the string. When a string is spread out over a long distance, it isn’t too obvious, but when the pixels are clumped together in a matrix like this, it is very noticeable. This is avoided by having multiple sourced of power, not just at one end of the string.

Since the string of pixels are broken up to form the channel groups, as a minimum, power needs to be routed to each channel group. This already assists with avoiding voltage-drop, since the long string is broken up, and each string is a shorter overall length. With each string only being 96 pixels in length, this was probably short enough that voltage-drop would not be a problem, but I was taking no chances here! I made it so that each string that had 96 pixels was powered at the start and the end. The two channels with 24 pixels were short enough that power was only applied to the start.

![]()

Rear Connectors

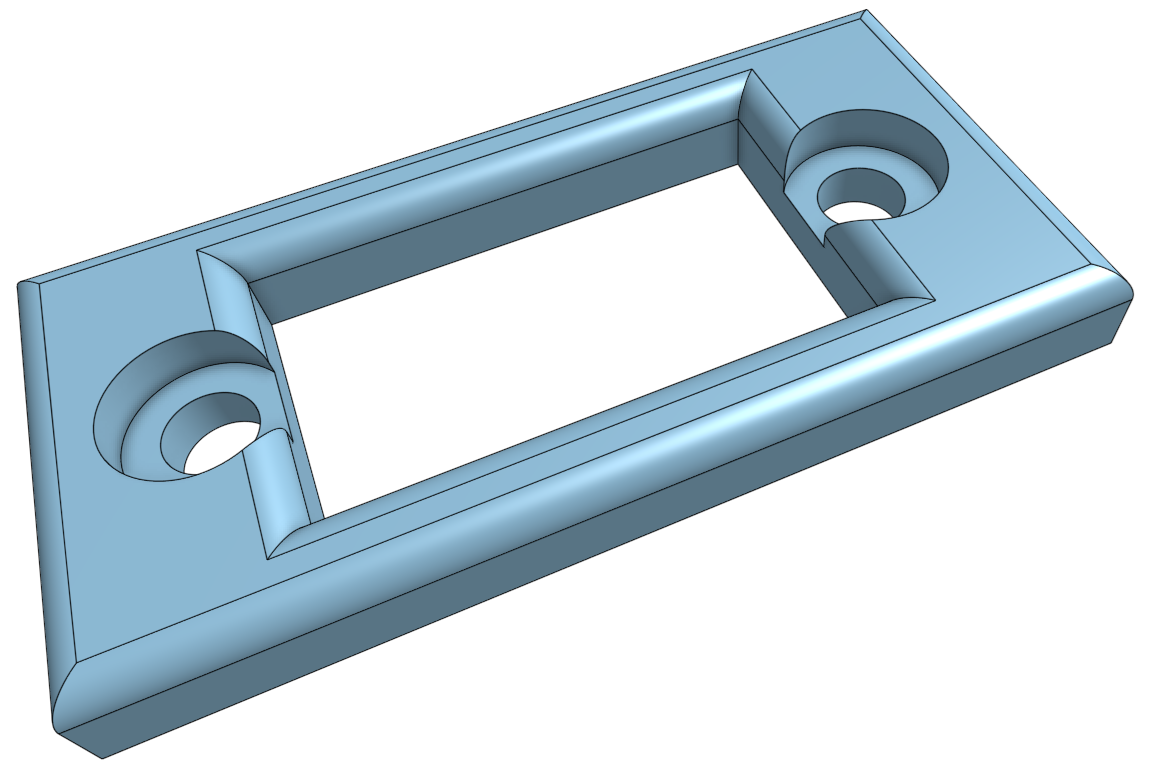

When designing these panels, I am keeping maintainability in mind, i.e. making sure that future-me does not hate present me! The back panel fits into the recess of the frame, and so I need to make sure that the connectors can be detached from the panel easily - if the connectors cannot be detached then it will be really difficult to remove the back panel with the connectors still connected to the wiring. For the data connectors, I chose the Switchcraft EN3 connectors - they’re a nice circular connector with a bayonet type attachment, and very conveniently, I had a pair of them in my box of miscellaneous connectors! The socket is a panel-mount type, which mounts on the rear and is affixed with a hex-nut. This is perfect as it means that should maintenance be needed, the hex-nut can be removed so that the connector stays with the wiring and the panel comes off completely.

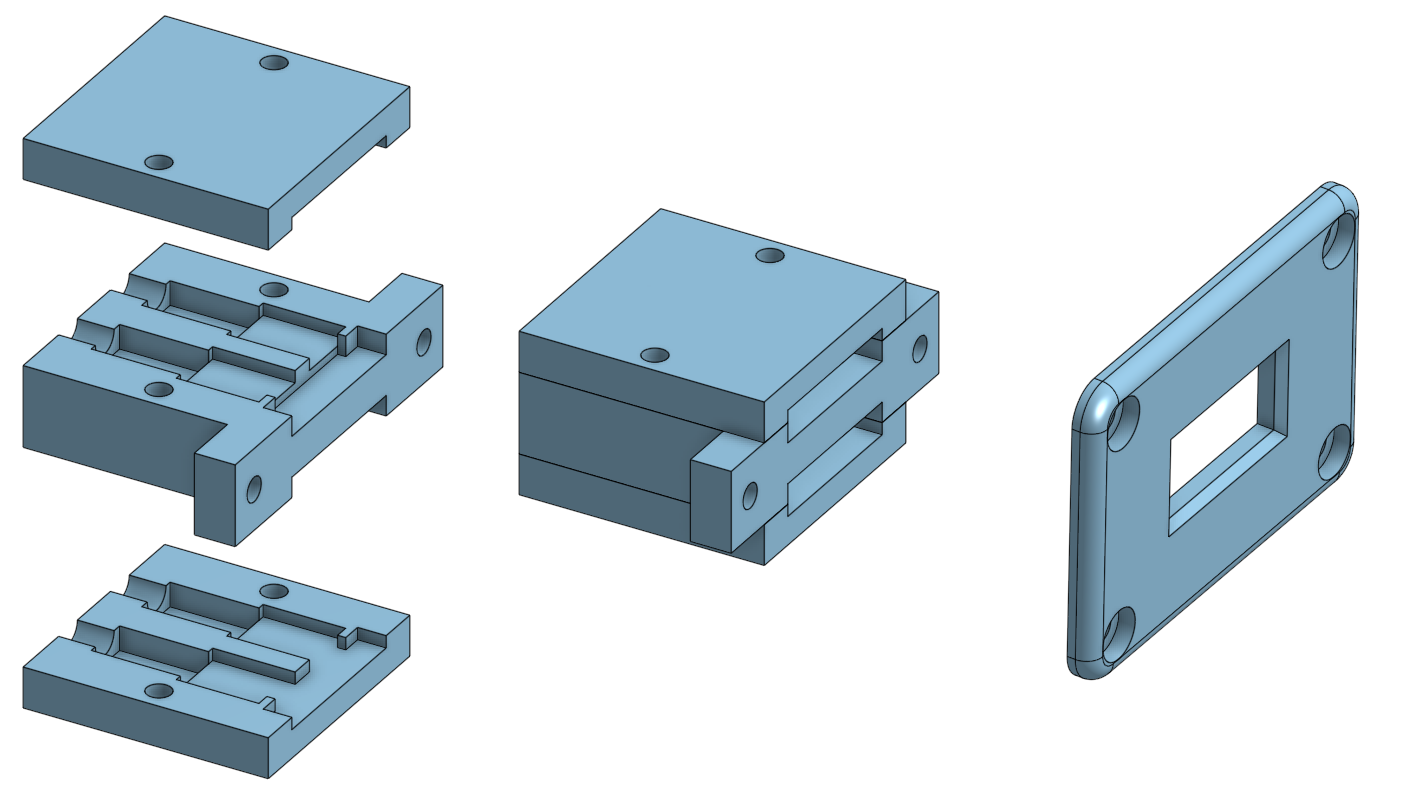

The only issue here, is that this panel-mount socket has a maximum panel thickness of 3mm, and my back panel is 5mm thick - damn! Well this was easily solved; I designed a panel in my favourite 3D CAD package, OnShape, which attaches to the back panel, and has an aperture for the socket that is 3mm in thickness. This is actually a better solution than mounting to the wood panel directly, because I am able to put the flat edge detail in, so that the connector cannot twist when mounted, which would strain the wires and connections within the panel. When I 3D printed this, I realised that there was actually a little more give in the mounting than is specified in the connector data-sheet, so I changed the panel to be 4mm thick. This means that the connector does not protrude as much, making it a little less susceptible to damage.

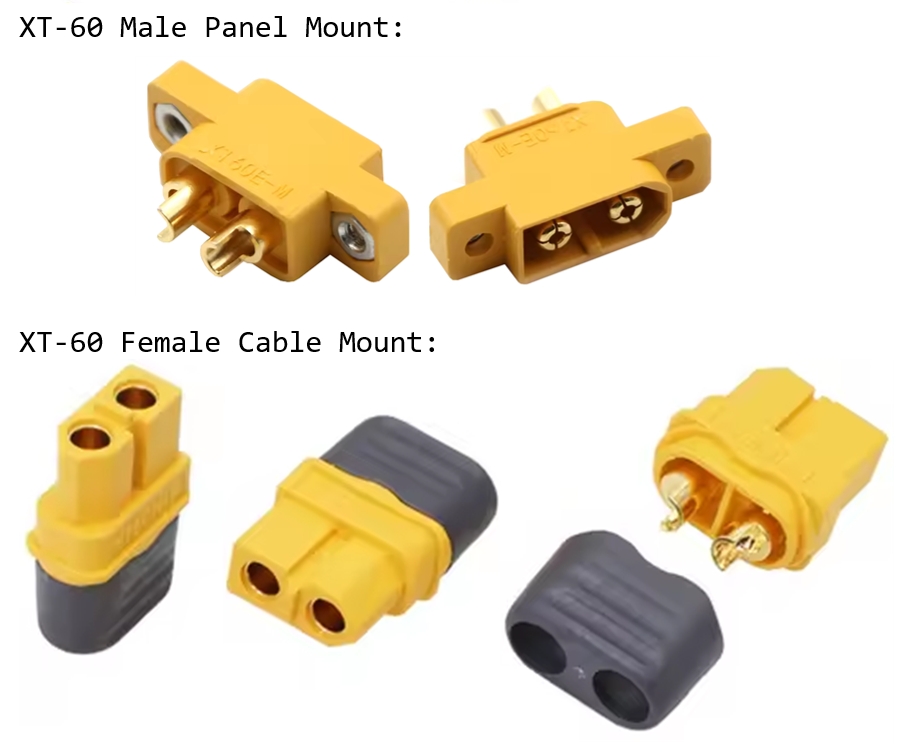

For the power connectors, these need to be robust and be able to sustain the high current demands of the panels. Each pixel is a RGB LED, so three LEDs in one. When each panel has all LEDs driven at full brightness (i.e. white), the panel should consume 23.4 A. I’ll be covering the power aspects of the design later in this post though. I had some familiarity with the XT type connectors, which are simple, robust, and are designed for high-current applications. I could have got away with using XT-30 connectors, which are rated for continuous current of 30 A, but I decided to go with the XT-60 connectors instead, which are rated for continuous current of 60A. It isn’t the current rating that made me go for the XT-60, it is because it is bigger and is less fiddly to connect - makes it easier to set up.

A male panel mount XT60 is used for the power input on the panels (Since power outlets should always be a socket, and inlets a pin). I decided to design a little mounting panel for the power connector, again, using OnShape and my 3D printer. This means that there is a bigger surface of attachment than if I just used a nut and washer. It also makes the overall appearance look more professional than the XT-60 poking out a square hole cut in the back panel.

The image below shows the final result of the connector mounting. It is shown here with the cables connected. As you can see, I used heatshrink to finish off the power cable.

Driving the Pixels

With the panels built, it is now time to build a box that can drive them so we can have some pretty effects on this LED Matrix! In case you were wondering, I did test each channel group to make sure that all the LEDs were working!

Pixel Power

The WS2811 strings I have are specified to use a maximum of 0.3 W per pixel when the Red, Green and Blue are at full brightness (i.e. full white). With 624 pixels, this will be 187.2 W. Also in the data, it specifies that the maximum current consumption of 60 mA (makes sense, 20 mA per R/G/B). Multiplied by 624, this is 37.44 A. Since they use 5V, the power is 37.44 A × 5 V = 187.2 W - the same value as before - phew, that’s a relief, since I was dubious due to the data being on an AliExpress page!

A pretty beefy 5V PSU is needed, and it needs to be de-rated. In a nutshell, I don’t want the PSU to be operating close to its maximum specified power - this is very standard practice. It prevents the PSU overheating, and ensures reliability; operating a PSU at its maximum is a sure-fire way to reduce its lifespan. So, in worst case scenario (i.e. Pixels at their maximum) I only want the PSU to be operating at a maximum of 80% of its stated power, ideally lower. So, if 187.2 W is 80%, then 100% is 234 W, similarly, if 37.44 A is 80%, then 100% is 46.8A. I.e. the PSU needs to be at least 234 W / 37.5 A.

When I looked for a suitable PSU, chose a 300 W 60 A one, since the one below that is 200 W, which isn’t high enough. This is good, since it means that the PSU is even more de-rated. So, when the panels are at their maximum power of 187.2 W, the PSU is at 62.4 % of its full capacity, so that’s great, the PSU is never going to be under heavy load and it should mean a long life-span.

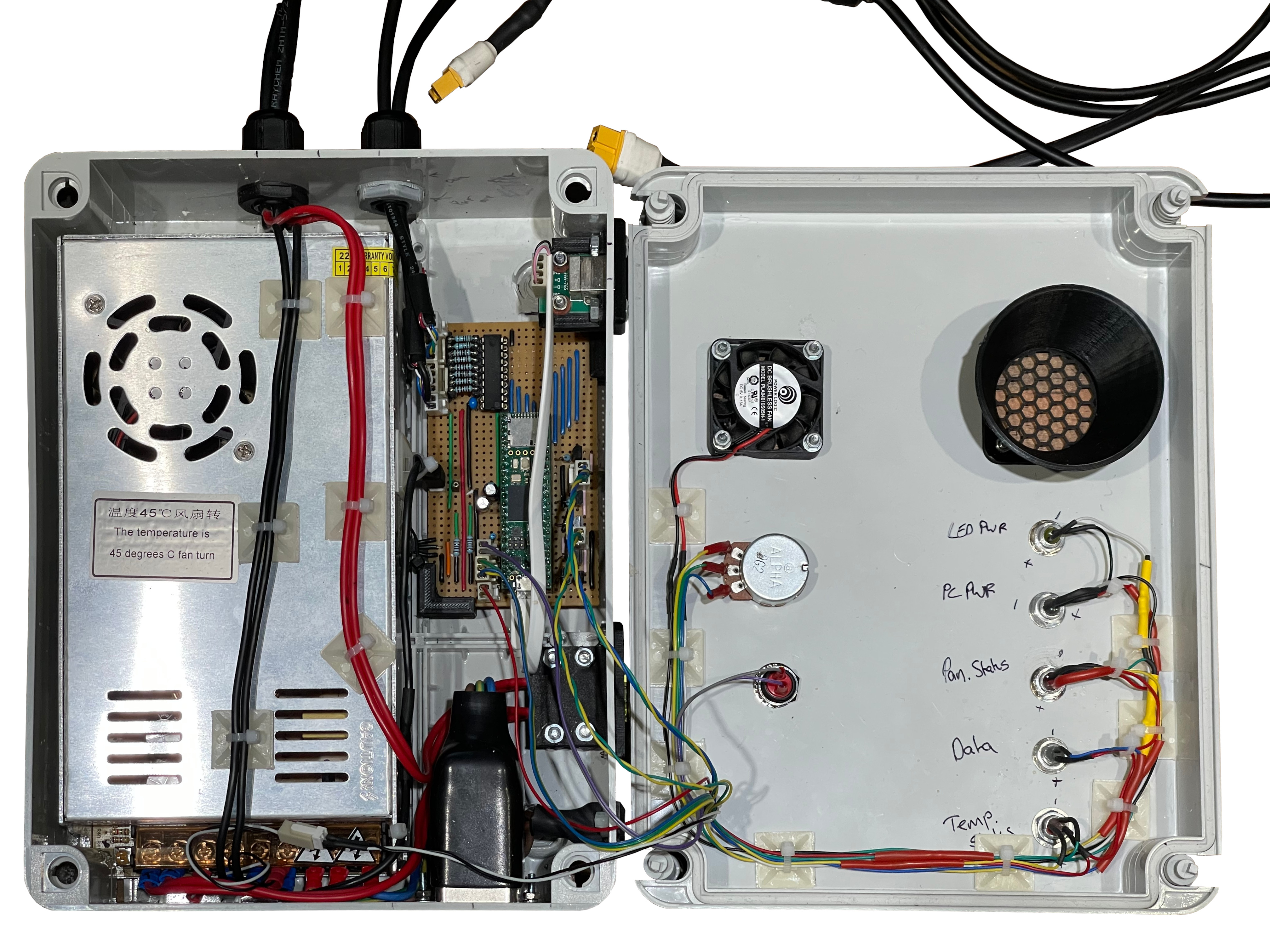

Packaging It Up

The idea is to have a “control box”, which houses the PSU and the Microcontroller board as an all-in-one centre for the Matrix Panels. The main factor governing the size of the control box is the size of the PSU. Now, I don’t know if you have ever tried to look for a suitable enclosure for a project, but I find that it can be blooming difficult sometimes and time consuming! Are those internal dimensions? Are those external dimensions? Gah! I eventually settled on a Gewiss Surface Mounted Plastic Enclosure, part number GW44208. It has external dimensions of 254 × 200 x 98 mm, and internal dimensions of 240 × 190 × 90 mm.

![This is the enclosure I chose. Nice, isn't it? [sarcasm] Enclosure](/blog_images/odl_led_matrix/Enclosure.png)

On the face of it, this is big enough for the PSU, however it has noggins (correct term?!) in the corners for the lid screws to go into - this means that the PSU cannot butt-up right to the edge. All is not lost though - I realised that I can cut a notch out of one of the noggins, and modify the connector-end of the PSU enclosure to be able to accommodate the PSU, since it is below the screw depth. This is more clear in the following photo of the PSU mounted in the enclosure:

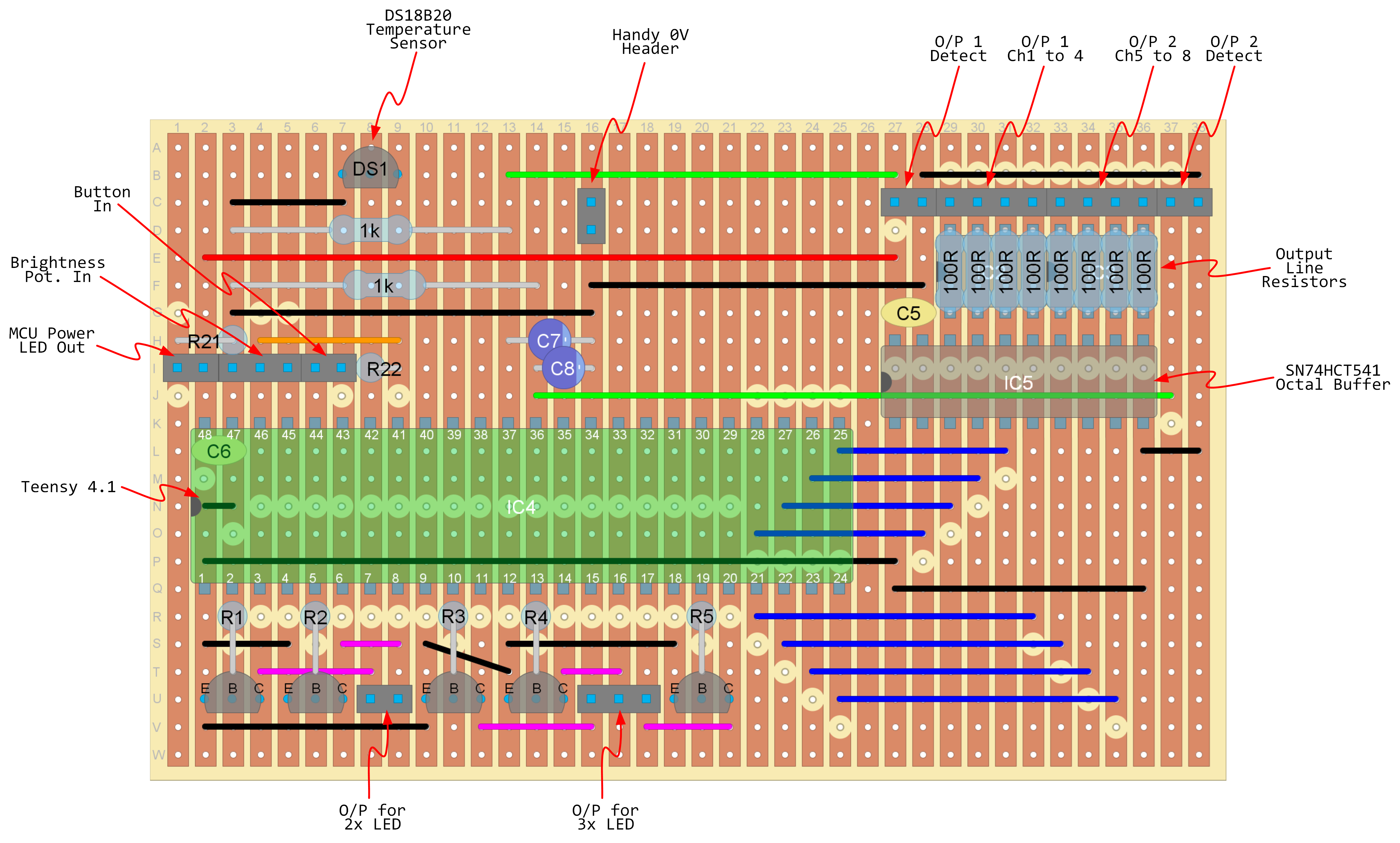

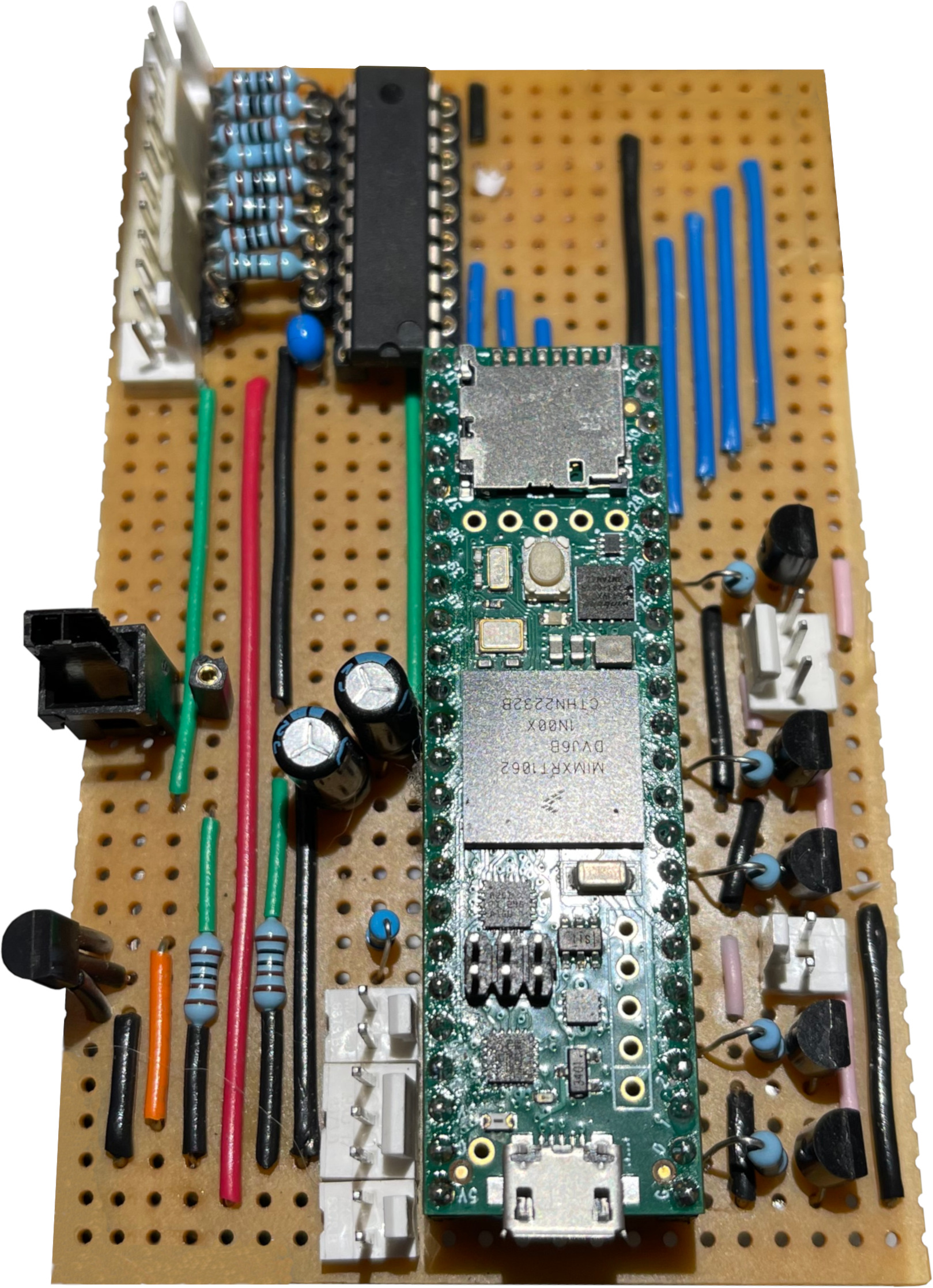

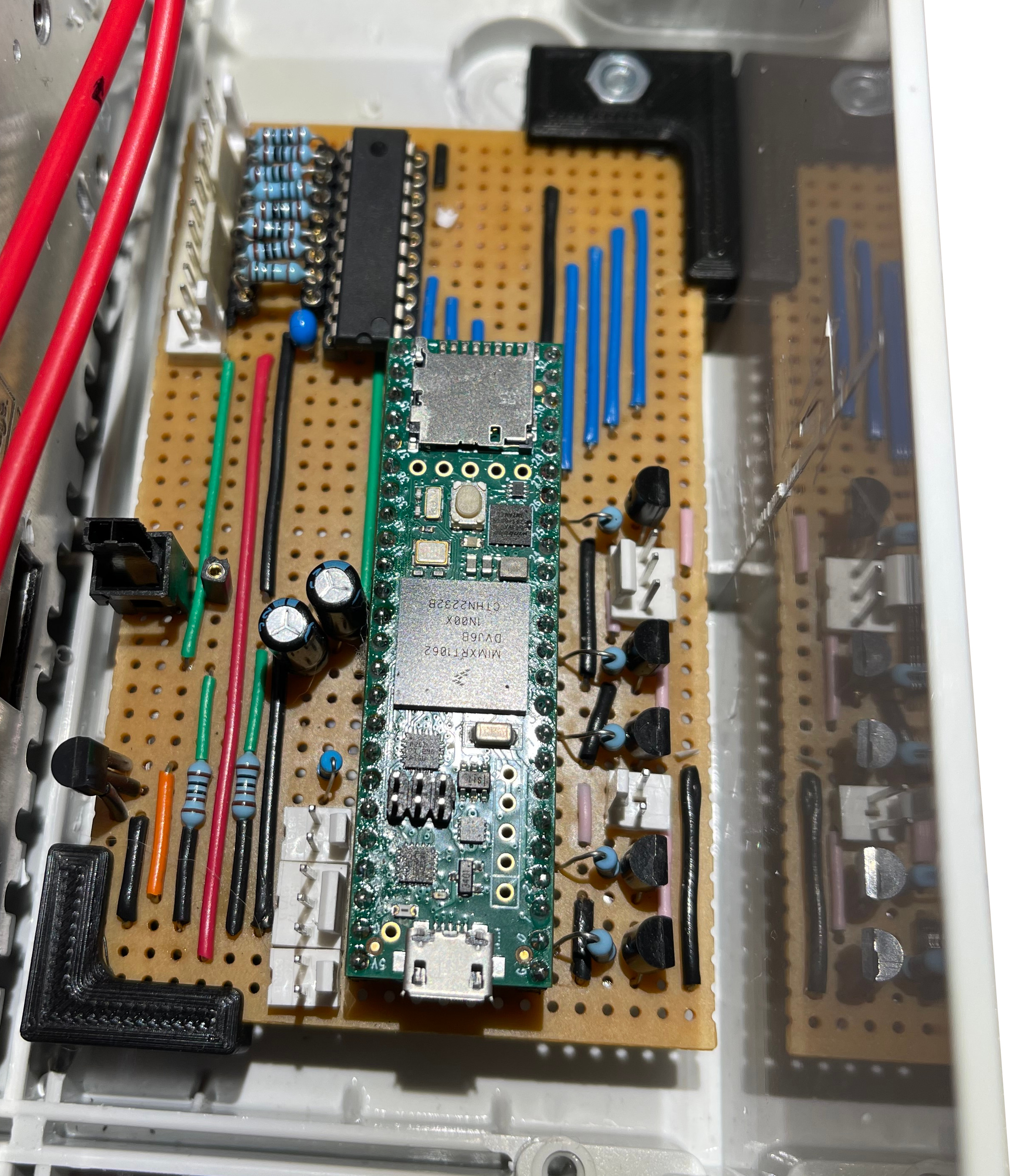

Microcontroller Board

With the PSU fitted in the enclosure, I now need to squeeze in board that has the Teensy 4.1, and associated support circuitry. I’ll break it down:

Output Buffer

As previously mentioned, the Teensy 4.1 is a 3.3 V device, so its GPIO outputs are 3.3 V at logic high output. The WS2811 Pixels take 5 V, and in general, require a 5 V logic data signal. If we go into nitty gritty detail, the WS2811 IC is specified to have a VIH minimum of 0.55VDD. VIH minimum is the threshold at which the input is registered as a logic high input. So, when VDD = 5 V, VIH minimum = 0.55 × 5 V = 2.75 V. So, technically, the WS2811 ICs will handle a 3.3 V logic input, but, there is only 0.55 V of headroom there - I’m not happy with that.

To solve this, I need to convert the 3.3 V logic out of the Teensy 4.1 to 5V logic. I decided to use a TI SN74HCT541 Octal Buffers and Line Drivers with 3-state Outputs. Why this? Well, it can operate on supply voltages between 4.5 V to 5.5 V, for registering logic high inputs, the threshold is VIH minimum = 2 V, so the 3.3 V logic output from the Teensy comfortably surpasses that. For registering logic low inputs the threshold is VIL maximum = 0.8 V, the logic low output of the Teensy 4.1 should be pretty close to 0V and will never be anywhere near that threshold.

How about the output? Well, the WS2811 datasheet defines the data in pin as consuming only 1 μA. (I’m not sure how much I believe this, since that would mean the input impedance is 5 MΩ! Hmm.) Well, taking it at face value, when the output current of the buffer is 20 μA or less:

VOH = 4.4 V min @ 20 μA

VOL = 0.1 V max @ 20 μA

… That’s much better! The logic high output is guaranteed to be at least 4.4 V, and in reality, probably much closer to 5 V, since the stated values are a conservative minimum. I will have the enable pins permanently asserted, so the 3-state output functionality is not used. I absolutely love this choice of buffer by the way, it’s classic 7400 series logic, it’s been around since the 60’s. In fact, the datasheet linked was first written in 1996 when I was 5. This is the HCT version, but I suspect the original ‘541 was probably released between the 60’s and 80’s. (I’ll try find out…).

With WS2811 LED Strings that are located away from the data source, the most vulnerable part is the link from the output to the first pixel, and indeed this project fits this mould. The outputs from each pixel are buffered outputs from the WS2811, and the wire distance between each pixel is the same, and short. So, we need to ensure that the data that reaches the first pixel does not suffer from any signal integrity issues. Admittedly, the signal is quite slow when compared to high speed links where signal integrity is a real concern, so there is not as much danger, however signal integrity issues still can cause problems. Having the output buffered to be 5 V logic certainly reduces potential signal integrity issues, however it may be necessary to have low value impedance matching resistors in-line with the outputs to help balance out any signal integrity issues. I was not sure if this would be needed or not, so I decided to design them in using single in-line sockets, so that I could observe the input data at the first pixel on my oscilloscope both with and without impedance matching resistors, and make the call whether they are needed or not.

Status LEDs

I decided to put some status LEDs on the control box. These being:

- Status - Red/Green LED

- Temperature Status - Red/Green LED

- Data - Blue LED

- Matrix Power - Green

- Microcontroller Power - Green

The latter two are sourced from power rails, but the first three will be driven by the Teensy, i.e. 5 outputs. The Teensy GPIO pins cannot output the required current for the LEDs, so will need buffering. I decided to use some NPN transistors that I had in my box of bits, allowing me to wire these up with common anode to the 5V rail. Standard 2N3904 NPN transistors are used, with 1k on the base input.

Panel Detect Functionality

This is a nifty feature that I decided to add in - I had some spare cores in the data cable, so I decided to make it so that the microcontroller can detect which panel is connected to each output plug, since they’re both the same. It’s quite simple really, there are two analogue inputs that are pulled low by a 1k resistor. These two input lines go to the panels. One of the panels has this line to 5 V via a 1k resistor, meaning this panel cause a 2.5 V reading (Remember, the Teensy is a 3.3V device so we cannot put more than 3.3V into an input). The other panel has the line to 5 V via a 3k resistor, meaning this panel will cause a 1.25 V reading. If the connector is not connected to a panel, 0 V will be read.

Temperature Readback

Temperature could be a concern in this control box enclosure - I can mitigate this vents and fans should it be a problem, but I thought it was a good idea to put in some way of measuring the ambient temperature in the control box. Two reasons for this; during development and testing, I can use it to keep an eye on the temperature and make amendments as necessary. The second reason, is one that I hoped I would not need, but if temperature was a real problem, then I could add functionality in the code to throttle down the brightness should the temperature be too high, to reduce the demand on the PSU. Speaking of brightness control…

Brightness Control

The LED Pixels are quite bright! The brightness of the pixels can of course be controlled in firmware, but I did not want to hard-code this as a fixed value. A brightness control seemed a good idea. This is implemented very simply! I will have a rotary potentiometer that is connected across 3.3V and 0V (5V is a no no!), and the wiper of the potentiometer is readback on an analogue input. This analogue readback can then be used change a brightness variable.

User Button

I did not see any need for a button on the control box, but I did not know if I may want one for a future upgrade to the firmware (for some feature I haven’t thought of yet). To make sure that future-me likes present-me, I added a push button into the design. It won’t do anything, but it is there just in case! I decided to utilise the built-in pull-up on the GPIO pin to save me from needing to add a pull-up/pull-down resistor on the board. The button simply connects between the input and 0V.

Board Design

I wanted to keep costs down on this project, so I decided against having a PCB made, and instead use stripboard. I had limited space available in the control box enclosure now that the PSU is fitted, so I measured what was available and designed with this constraint. To plan the stripboard, I used DIYLC - I’ve been using this for the last 15 years, and honestly it has never let me down. For me, planning and preparation of stripboard always results in really neat and tidy designs, that usually work first time! I’m quite proud of that to be honest.

The following table shows the pins that are utilised on the Teensy 4.1 for the functionality discussed:

| Pin No. | IO No. / Net | Special Function Used? | Connected to |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | GND | - | GND / 0V |

| 2. | 0 | GPIO Out | Status Green LED |

| 5. | 3 | GPIO Out | Status Red LED |

| 10. | 8 | GPIO Out | Temperature Status Green LED |

| 13. | 11 | GPIO Out | Temperature Status Red LED |

| 19. | 27 | GPIO Out | Data Activity LED |

| 21. | 29 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 1 |

| 22. | 30 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 2 |

| 23. | 31 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 3 |

| 24. | 32 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 4 |

| 25. | 33 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 8 |

| 26. | 34 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 7 |

| 27. | 35 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 6 |

| 28. | 36 | GPIO Out, Direct DMA Write | WS2811 Ch. 5 |

| 34. | GND | - | GND / 0V |

| 36. | 14 | A0 | Panel Detect 1 |

| 37. | 15 | A1 | Panel Detect 2 |

| 42. | 20 | 1-Wire Bus | DS18B20 Temperature Sensor |

| 44. | 22 | GPIO In, Pull-up enabled | User Button |

| 45. | 23 | A9 | Brightness Pot Readback |

| 46. | 3.3V | - | R22 Pull-up for DS18B20 & Brightness Pot |

| 47. | GND | - | GND / 0V |

| 48. | Vin | 5V In | MCU Power LED, Via R21 |

The Board Exists

Built the board to my plan, no troubles there. For the connectors, I used Molex KK254 type connectors. I love those, I use them all the time. Have a selection of them to hand at all times!

The Teensy 4.1 isn’t soldered directly to the board, since that’s silly. The Teensy sits in a header socket.

Time to Code

The code to drive these panels went through many versions! I’m going to try and not waffle on, and explain the key points.

As a first test, I of course wanted to see the panels working using some basic effects built into the firmware. I used the OctoWS2111 Library by Paul Stoffregen to accomplish this.

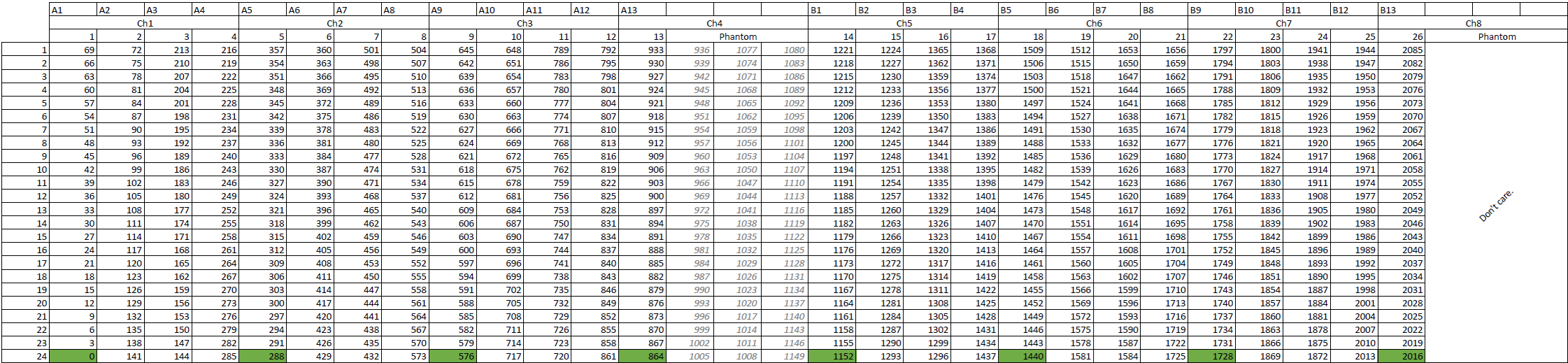

Setting this up with Jinx! was a little tedious - each pixel is three channels; Red, Green and Blue. That means the first pixel occupies channels 0, 1 and 2, the second 3, 4 and 5, and so on. Couple this with the serpentine layout, and it quickly became very confusing. Also, to simplify things, for the two channels that only have one column, I decided to approach it from the perspective of them having three phantom columns, these being columns that don’t exist. Using the phantom columns/pixels kept things simpler overall, by making all eight channels drive the same number of pixels…kind of.

To try and make this easier, I mapped it all out in a spreadsheet.

My first attempt at driving the panels from the Jinx! software was using ArtNET over Ethernet, using the Ethernet Kit for Teensy 4.1. It kind of worked, but it was a bit temperamental, and can safely point the finger of blame at my code, I’ll accept that! I could have fixed this, but there was something bugging me - I was developing this on my Windows laptop, which has an Ethernet port, however the Windows 10 Tablet I had for this project did not have an Ethernet port. This means that a USB to Ethernet dongle would be needed. I didn’t like this - anything that can go wrong will go wrong, and a USB to Ethernet adapter will go missing at some point. That’s a weak point in this system.

So, I felt no shame in scrapping the ArtNET connection idea, and instead focussing on using the USB UART on the Teensy 4.1. Remember, the USB UART on a Teensy 4.1 is not limited by a traditional Baud rate of conventional UART; it actually runs at native USB speeds, so this is a massive relief.

The most sensible option here was to use the TPM2 protocol, which is a protocol designed for LED Matrices. This is where the TPM2 Arduino Library by rstephan came in extremely useful.

Up to now though, I am just using the OctoWS2811 library to drive the pixels, which is great, and it works. But, FastLED exists! FastLED is one of the best libraries for driving WS2811 pixels - I’d recommend checking it out, to see why. I wanted to be able to use this! I needed to therefore combine OctoWS2811 with FastLED. Quite fortunately, I came across this great resource, which allowed me to accomplish this. You can see the test in the video below!

Rather than explain all the code here, It’s probably best to go check it out on my GitHub Here - I’ve explained it all in the comments.

Coming back to the data-line resistors, I observed the data arriving at the first pixel on an oscilloscope. I found that the signal was marginally better with 100Ω resistors. So these will stay. I soldered them into the sockets so that they won’t become loose. Unfortunately I don’t have a photo of the oscilloscope results, so you’ll just have to trust me! Sorry.

Finalising the Control Box

Now that I know that it all works, the Control Box needs to be finished off.

For the Mains Input, I mounted a panel mount IEC C14 connector. The one I used had built-in fuse and was also an EMC filtered one. You guessed it, I had it amongst my collection of parts! I also fitted a panel mount flip-switch in series with the Live, to allow the power to be easily controlled - also from my collection of miscellaneous switches.

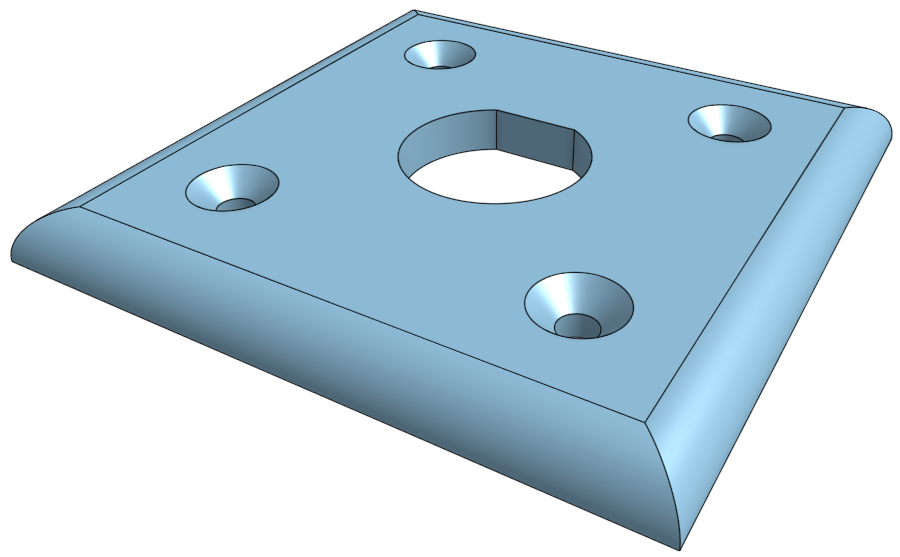

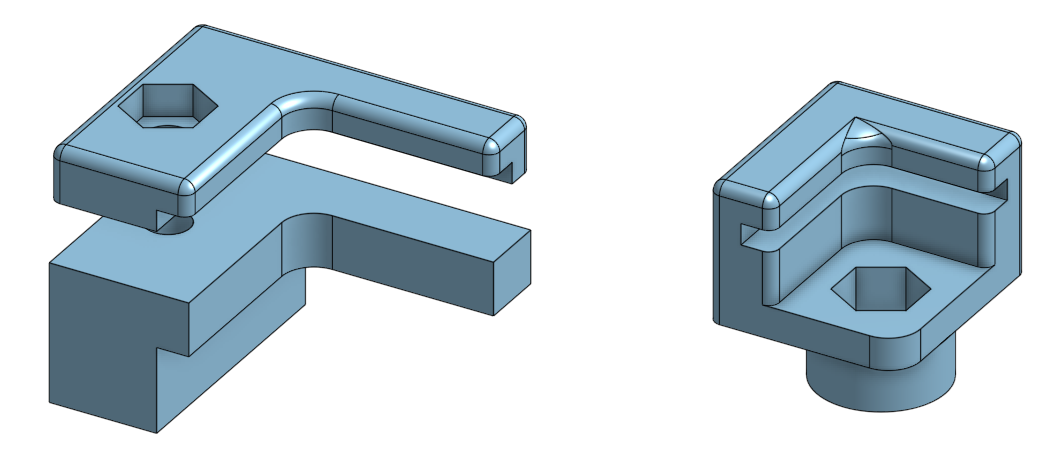

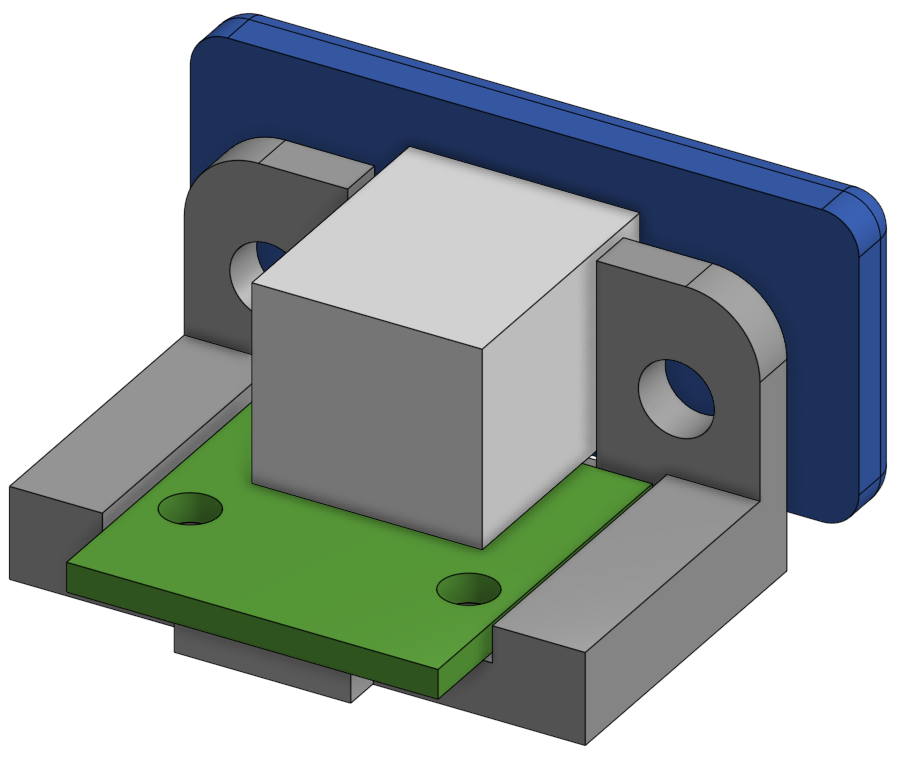

For safety, I wanted to add fuses for the power to the panels - the PSU can supply 60 A after all! There’s two power cables for the two panels, so I wanted two fuses, one for each panel. I wanted to use automotive blade fuses, since they are cheap and readily available, and changing them is tool-less. I wasn’t able to find a dual blade fuse holder, so I bit the bullet and designed my own. The handy thing about blade fuses is that the terminals fit into fast-on spade type connectors, so I designed my fuse holder to use these. In a nut-shell, I took precise measurements of the fast-on spade receptacles I had, and made my design around that, such that the connectors fit in the fuse holder exactly. Side note - fast-on spade crimps from Amazon are absolute junk! Scary when these are commonly used for mains. Thankfully I had some quality ones in my stores. Link to OnShape Part

With the microcontroller board, since space was at a premium, I did not have much space to allow for mounting holes. I purposefully didn’t even bother trying to accommodate mounting holes, and instead knew that I’d mount them with some 3D printed hardware. I created two mounts that hold the board by opposite corners - one of them is fixed and the board slots in, and the other one comprises of two parts, the board sits on top of the bottom fitting, and then is fixed in place by a top part. This means that the board can be removed with just one screw, if needed. OnShape Link to Part

After printing these, I fitted them into the control box:

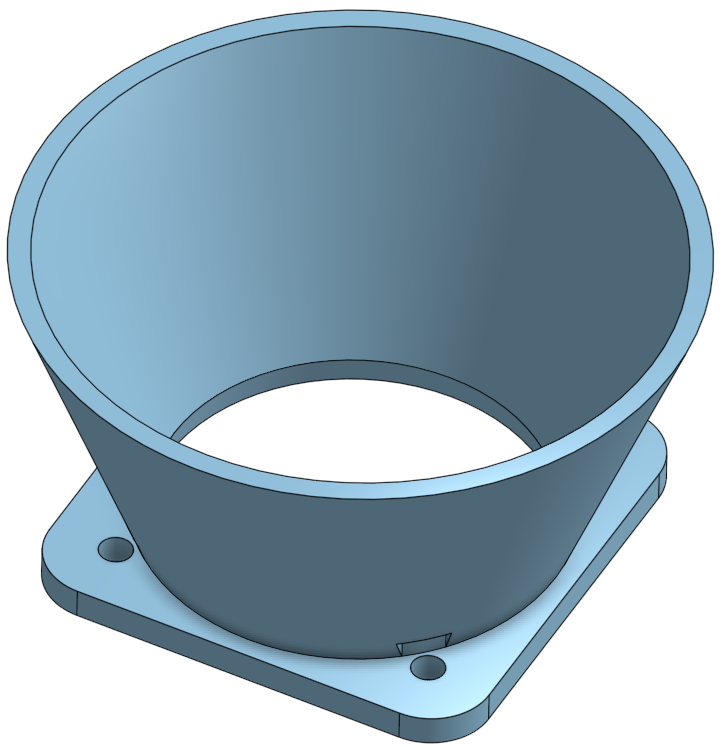

And let’s not forget about the USB connector, that’s pretty important! I decided to use a USB-B socket for connection, Mini-USB is dead, and Micro-USB is too flimsy. I probably should have put a USB-C connector on this, but when I was making it, I wasn’t really in the USB-C bubble at the time, and I had one of these available to use:

It’s not very panel mountable though, so I made a holder and facia for it in OnShape. I even got a bit fancy and made a model of the USB B Connector Module too! OnShape Link to Part

I decided to put a fan on the box, to aid with keeping the control box cool. The PSU already has a fan that kicks in when it gets hot, but it just vents within the box. I didn’t like that, so I designed a duct assembly that will sit over the PSU Fan, and directs airflow to the outside. OnShape Link to Part

And that’s the Control Box done!

Jinx!

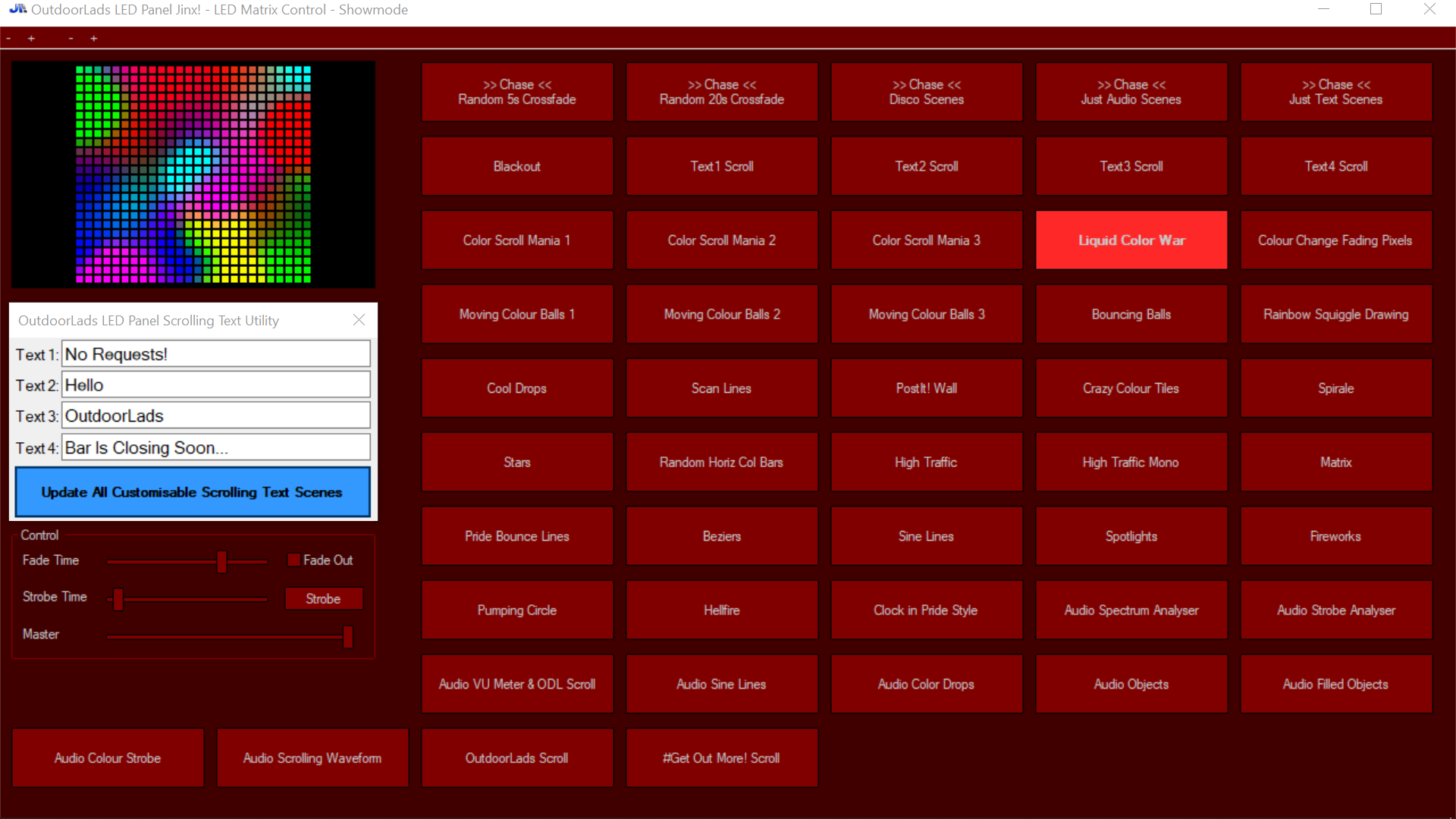

With the Matrix Panels now doing what I want, I need to sort the Windows 10 Tablet that drives these panels. As mentioned, I am using the Jinx! software. You can create effects, and merge effects together. It’s very powerful - the instruction manual is very good too, it’s worth a read if you’re curious about Jinx!. Very conveniently, it comes with a bunch of effect that are totally awesome! When you have a bank of effects made, Jinx! allows you to create a “Show Mode” control panel. Many of the effects that come with Jinx! made it into my show mode control panel.

One nice feature of Jinx! is that it allows you to show scrolling text. But the annoying thing is, you cannot update the text when you’re in show mode. What I wanted, was a way to display scrolling text, and be able to edit it from the show mode control panel. I came up with a neat work-around though - you can configure Jinx! to read in the text from a .txt file for the scrolling text, and I discovered that when the .txt file is updated, the scrolling text is also updated too. That’s really exploitable! I used Visual C to make a little dialog box with four text boxes. When the enter key is pressed (or on-screen button tapped/clicked), four .txt files are updated accordingly. With Jinx! set to use these four .txt files, the text can be updated easily. I also made it so that this window automatically positions itself over some controls that are not needed, and also so that the dialog box is perpetually kept at the front (i.e. so it doesn’t disappear behind Jinx!). I compiled this into an .exe file, and made a little wrapper .bat file on the desktop, so that the .exe and Jinx! are loaded together. Shown below:

START c:/jinx/jinx.exe -m c:/jinx/OutdoorLadsV3.jnx

START c:/jinx/ScrollingTextUtility.exe

Below is a screenshot from the tablet of the show mode control panel. I made the colour theme dark red for two reasons; firstly, it reduces brightness from the screen, you don’t want a bright screen at your side when you’re DJing, and secondly, it is very on-brand with OutdoorLads.

Actually, before I made the text utility in Visual C, I made it in Python. It worked, it was great. But you know what wasn’t great? For some reason, the Windows on-screen keyboard would not pop up for the text boxes. I tried to figure this out, and came up empty handed. I guess there mustn’t be many cases of people wanting the Windows on-screen keyboard with a Python GUI! Rather than waste hours on this, I went the Visual C route. Brushed up my Visual C skills in the process so this was kind of beneficial.

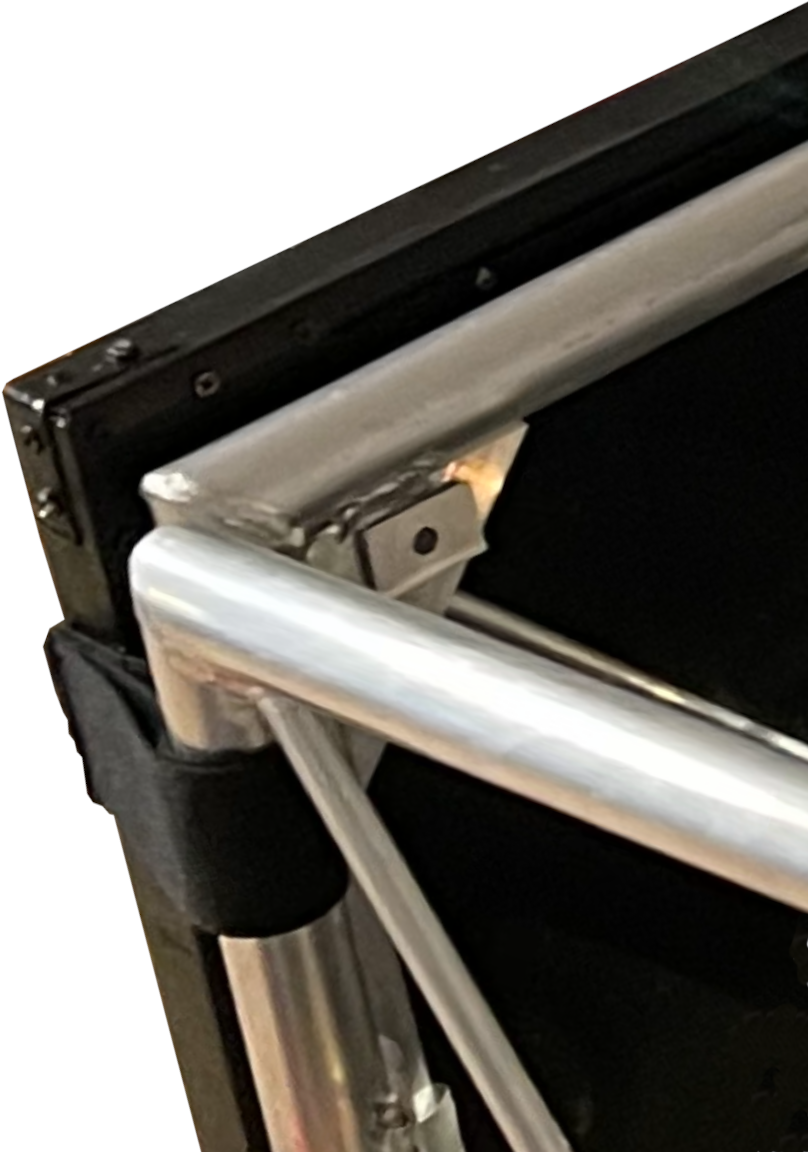

It’s done!

With all that, the project is nearly finished! The final thing to do was figure out a way to attach the panels to the DJ Booth Truss. I kept things simple here, and used some heavy-duty Velcro straps. I cut them to size, used a sewing machine to tidy up the cut ends, and attached these to the panels with wood screws. Overall, it works really well, see below:

Okay, it is finished!

Version 2 Time…

So, I’m really pleased with the result, it looks absolutely amazing. But I discovered two problems, which fortunately work together. When I was developing, I was using my Windows laptop to drive the panels using Jinx!. It worked absolutely fine, no problems. Unfortunately it was not plain sailing with the Windows 10 Tablet… For some reason, after what seemed like an arbitrary amount of time, the USB communications would die. There is a blue LED on the control box that shows when data is being received, and when the USB communications died, this LED was off. This was super annoying, it worked fine on my laptop!! Restarting the output in Jinx! would fix this, but it would always eventually die. I can only imagine that for some reason, the Tablet is putting the USB into standby, or something like that. I changed some settings on the USB Host on the Tablet, which I thought had fixed it, but it didn’t.

Damn! But that leads me onto the second problem - It hit me that I had over-engineered this with the tablet. One of my requirements was that it “Must be easy to setup by non tech-savvy people”, and as much as I hated to admit it, I think the tablet just over-complicated things. Plus, who really wants Windows 10 to be part of a solution?! Although I’d made the operation of the tablet streamlined, it was still a bit faffy. And the tablet mounted to the side of the DJ booth was a bit clunky and just added another setup step.

I made the decision that I should simplify this. This should just be a plug-and play system - plug the control box into the panels, plug in the power, turn it on, and it works. But the problem is that I have all these amazing effects that are generated by Jinx!, and I did not want to lose these.

Well, here is where that micro-SD card slot on the Teensy 4.1 comes to the rescue! What I did, is create a Jinx! chase that cycles through all the effects, minus the ones with custom text, and redirected the output to record the serial stream to a file. I then changed the firmware so that instead of reading in the data from the TPM2 serial stream, it reads it in from the file on the SD card. When it gets to the end, it simply starts again from the beginning. This was perfect - I had the same fancy effects from Jinx!, but no need for the tablet - easy plug and play!

Take a look at the firmware for the SD Card version on my GitHub Here.

Okay, now it is finished! :)

Requirements Check

Must fill the whole front of the DJ Booth, and be able to be securely attached

Yes! Fills the entire front, and is attached easily with heavy-duty Velcro straps.

Must be able to fold up to aid in transportation and storage

Yes! When folded up, it is 1150 × 605 × 50 mm. Folds on hinges, and secures closed with hasps.

Must be rugged to withstand transportation and drunk people

Yes, I think it is rugged. As for drunk people, as of now it has been used for 2.5 years and no problems yet.

Must be easy to setup by non tech-savvy people

First version, No. Second version, Yes.

Must have a decent pixel density (bit of a wishy-washy requirement)

I think so. Design A was not dense enough, Design B was probably too dense. I think Design C struck a nice balance, and the finished matrix looks good to me.

Must have a selection of kick-ass visualisation effects

Yes - thanks, Jinx!!

LEDs must be RGB, and be as big as possible

Yes, and LEDs are 8mm diameter.

LEDs must be able to be driven rapidly to sustain a video-quality refresh rate

Yes - I think it managaes about 50 FPS. It looks very fluid and the refresh rate is not noticeable at all.

Total cost of parts must be below £300

Yes! Can you believe that? It cost a total of £275.22. Of course some of the parts were what I had in my collection, but these were not significantly expensive items. Annoyingly, I had to buy a special Dell PSU for the Tablet, which was £14.39, and the tablet mount was £17.50. Since scrapping the tablet, this is £31.89 of wasted cost - damn it! (I do wonder how much my time would have cost, haha)